1. Introduction

In 2000 a renowned smart city researcher Anthony M. Townsend postulated that ‘new mobile communications systems are fundamentally rewriting the spatial and temporal constraints of all manner of human communications’ (Townsend, 2000). Townsend goes on to argue that mobile phones threaten the very foundation of city planning by ‘reprogramming the basic rules of interaction for urban inhabitants' and enabling decentralised modes of urban control and coordination through micro-scale transformative processes (Townsend, 2000, p. 100).

Almost two decades later, mobile technology is indeed transforming various aspects of everyday life for many people around the world. According to GSMA Intelligence, there were over 5 billion unique mobile subscribers in 2017 worldwide with the number expected to rise steadily in the coming years (GSMA Intelligence, 2017). Particularly in China, in a span of a few years owning a smartphone has become a de facto necessary prerequisite for most everyday transactions (Mozur, 2016, 2017). In the Western world the disruption of everyday life through mobile technology has been more gradual. Now a virtually ubiquitous access to smartphones in metropolitan areas has significantly altered how urban dwellers interact with people, services, institutions and the city as a whole.

Airbnb and Uber are prominent examples of new types of services, colloquially grouped under the term sharing economy, that are fundamentally transforming housing and transportation markets in many cities. These smartphone-enabled digital platforms are disrupting urban dynamics by disintermediating traditional distribution channels. However, despite the rapid uptake of smartphone technology and commercial success of digital platforms, urban planners and policymakers which are not subject to competitive pressure have not kept pace with the industry and are slow to sensibly incorporate these novel modes of interaction into their designs and processes (Buccoliero & Bellio, 2010). The potential of mobile technology to disrupt entrenched bureaucratic systems, as alluded by Townsend, remains mostly untapped.

1.1 Research purpose and structure

This paper analyses existing smartphone solutions for participatory urban planning and examines their shortcomings in order to identify why is there a lack of notable innovations in this area. The analysis is used to infer guiding principles and best practices for designing and developing participatory platforms. The overarching aim of the paper is to provide set of design heuristics that can be used by individuals and organisations to develop citizen-first participatory platforms. The utility of the provided heuristics is illustrated on an interactive prototype.

The paper starts off by positioning the research within a broader context of the contemporary urbanism by critically looking at the dominant smart city narrative and by highlighting the importance of alternative visions of future cities based on participatory bottom-up approaches to urban development and innovation. Next, the research methodology is presented followed by the analysis of existing solutions and the establishment design heuristics for design and development of participatory platforms. The paper concludes with the presentation of a prototype and a discussion of results, limitations and suggestions for further research.

2. From smart city to smart citizens

Models and ideals of urban planning that have evolved over the last few centuries seem inadequate for the contemporary cities where ‘the spaces and rhythms are radically different to those described in classic theories of urbanism’ (McQuire, 2008, p. vii). Similarly to how aerial imagery gave planners a sense of omnipotence through a bird’s-eye view of the urban landscape in the 20th century, urban planner and city leaders today are seduced into grand visions of civil order through a top-down panoptical view of the city enabled through latest advances in ICT.

Expanding data collection capabilities that offer robust computational analysis of minute details of lives of city dwellers through networked sensors gave rise to a smart city ideal which has established itself as a leading conceptualisation for the urban way of life in the 21st century. Despite extensive literature and media coverage, the smart city as concept lacks a single point of origin and is shrouded in a conceptual uncertainty. Townsend (2013) describes the smart city as a place where information technology is combined with infrastructure, architecture, and everyday objects to address social, economic, and environmental problems. Other closely related concepts include ubiquitous computing, ambient intelligence, ambient informatics, urban informatics, internet of things, sentient city, or computerised spaces (Graham, 2005; Greenfield, 2006; Waal, 2011).

Due to its ambiguity, the smart city as an idea has been co-opted by multinational companies as a means of corporate storytelling that promotes ICT products, services and infrastructure to a global marketplace of cities looking for technological solutions to their urban issues (Batty et al., 2012; Söderström, Paasche, & Klauser, 2014). Advanced under the guise of a prevalent neoliberal discourse these companies promise to rid cities of their inefficiencies by improving ‘safety, security, efficiency, antifraud, empowerment, productivity, reliability, flexibility, economic rationality, and competitive advantage’ (Kitchin & Dodge, 2011, p. 19). Adam Greenfield, one of the most vocal critics of the contemporary smart city rhetoric, goes as far as to suggest that the term appears to have originated with business ‘rather than with any party, group or individual, recognised for their contributions to the theory or practice of urban planning’ (Greenfield, 2013, par. 22).

As it is currently portrayed in the collective imaginary, the smart city is a technocentric approach to planning cities ‘rooted in stewardship, civic paternalism, and a neoliberal conception of citizenship’ which prioritises market-led solutions to urban problems (Cardullo & Kitchin, 2017, p. 1). This reductionist mindset is driven by the recent advances in big data analysis and machine learning capabilities of large-scale computational systems that stems in large part from an ideology that Langdon Winner refers to as cyberlibertarianism which a ‘collection of ideas that links ecstatic enthusiasm for electronically mediated forms of living with radical, right wing libertarian ideas about the proper definition of freedom, social life, economics, and politics’ (Winner, 1997, p. 14). A prominent historian Yuval N. Harari refers to this penchant for techno-solutionism as dataism which asserts that the entire universe can be reduced to data flows and that the value of any phenomena or entity, including humans, can be measured by how much it contributes to data processing (Han, 2017; Harari, 2017).

Fetishising data as something inherently objective, neutral and apolitical is at the core of surveillance capitalism that ‘is constituted by unexpected and often illegible mechanisms of extraction, commodification, and control that effectively exile persons from their own behavior while producing new markets of behavioral prediction and modification’ (Zuboff, 2015, p. 75; see also Han, 2017). Already firmly established in the production of digital spaces, this pervasive ideology based on data extravatism, glorification of engineering culture and techno-solutionism is increasingly permeating spatialities of everyday life and is establishing itself as a leading model for business and governance in the coming century (Cardullo & Kitchin, 2017; Greenfield, 2017; Han, 2017; Morozov, 2010, 2014; Zuboff, 2015).

The dominant smart city narrative based on technocratic principles of surveillance capitalism imposes a vision of clean, computed, centrally managed urban order that puts a combination of neoliberal, consumeristic principles and ideologies at the core of the smart city discourse. It is a profit-driven approach to developing and managing increasingly privatised cities through governance-as-a-service where citizens are treated either as consumers or a threat (Greenfield, 2013; Waal, 2011). From this perspective, citizens are reduced to statistics whose role ‘is simply to generate data that can be aggregated and subjected to analytical inquiry’ (Greenfield, 2013, par. 7) in which they become subject to a ‘modulation of their actions through software-mediated systems’ (Cardullo & Kitchin, 2017, p. 8).

Through increasing computational and sensing capabilities, the ‘code-based technologized environments continuously and invisibly classify, standardize, and demarcate rights, privileges, inclusions, exclusions, and mobilities and normative social judgments across vast, distanced domains’ (Graham, 2005, p. 563). Practices such as predictive policing, social sorting, micro-marketing, predictive profiling and anticipatory governance are already becoming commonplace in many cities around the world with China and USA leading the way (Cardullo & Kitchin, 2017; O’Neil, 2016; Wade, 2017; Wang, 2017).

The neoliberal vision of a smart city built on principles of omnipresent informatic and biometric modes of surveillance and disciplinary power enacted through ubiquitous computational awareness sets an unsettling precedent for the future of urban way of life (Bauman & Lyon, 2016; Foucault, 1975/1991; Han, 2017; Klauser, Paasche, & Söderström, 2014; Tucker, 2012). There is an urgent need to repoliticise the smart city discourse and introduce more inclusive and bottom-up approaches that ‘put citizens back at the centre of the urban debate’ (March & Ribera-Fumaz, 2016, p. 816). The following subsection looks at some of the core tenets of participatory urbanism with a particular focus on citizen participation through mobile technology.

2.1 The promise of smart civics

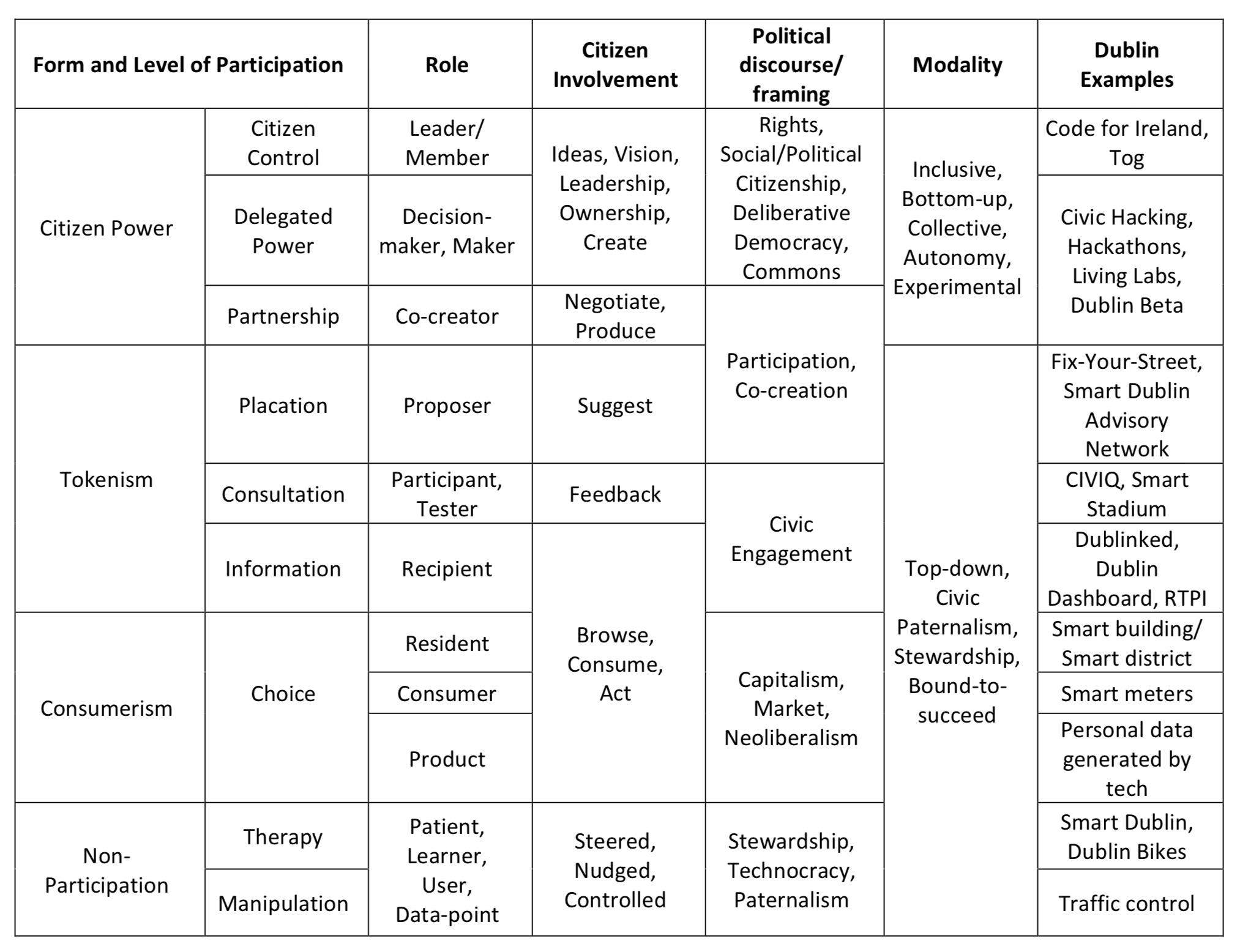

The citizen engagement and participation has been considered a cornerstone of good planning practice since the early 20th century when the inherently political nature of urban planning started to be more widely recognised (Seltzer & Mahmoudi, 2013). Involving citizens is based on a simple premise that 'those affected by plans should be engaged in making them' (Seltzer & Mahmoudi, 2013, p. 4). The ladder of citizen participation as proposed by Arnstein (1969) is widely used by researchers to assess the varying degrees and forms to which citizens are involved in the planning of cities. Cardullo and Kitchin (2017) who were looking at smart city initiatives in Dublin suggest a scaffold of smart citizen participation as a heuristic tool for evaluating smart city initiatives. The scaffold which is inspired by the original ladder from Arnstein is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Scaffold of smart city participation (Cardullo & Kitchin, 2017, p. 6)

Much of the direct citizen participation efforts to data fall into the category of non-participation, tokenism and more recently consumerism. However, a growing undercurrent of urbanism based on the ideals of collective participation, citizen empowerment, self-governance and technology-aided co-creation is challenging the paternalistic and market-driven notions presented earlier in this section. It is an approach that treats 'smart' in the smart city 'as an add-on, an upgrade, and not the end itself' (Townsend, 2013, p. 286). Here the city is conceptualised at the scale of an individual by sensitively leveraging networked technology to enable localised citizen micro-control and small-scale tactical urban interventions as opposed to grand city-wide schemes (Greenfield, 2017; Paulos, n.d.; Townsend, 2000, 2013).

Networked ICT infrastructure, social media and distributed technology offer a potential to push decision-making power closer to the people being most affected by the local urban development by improving communication and knowledge sharing across local communities, governments and professional industries. Integration and coordination of individualised and localised technology can lead to a synergy of personal and professional knowledge that will be necessary to build thriving cities in the future. Such an approach 'must involve ways in which the citizenry is able to participate and to blend their personal knowledge with that of experts' (Batty et al., 2012, p. 485).

A path towards better models of self-organisation and collective decision-making comes from a 'recognition that citizens should no longer be perceived as mere recipients of services, but as active players in the whole process' of urban planning and governance (Buccoliero & Bellio, 2010, p. 225). Rather than attempting to help and lecture citizens directly, such bottom-up models empower citizenry to help themselves through distributed technology (Kleinhans, Van Ham, & Evans-Cowley, 2015). Shepard (2007) uses the term propagative urbanism to describe 'aggregation of locally inflected, incremental modulations that have the potential to evolve into larger urban organizations' which he argues 'simply reflects how cities have always evolved' (par. 1). Seltzer & Mahmoudi (2013) use an analogy from a business strategy literature to view citizen participation as an open innovation that enables 'cooperative creation of ideas and applications outside of the boundaries of any single firm' (Seltzer & Mahmoudi, 2013, p. 5).

While the aims and ideals of participatory urbanism are clear in theory, they have yet to materialise on a significant scale. Brabham (2008) argues that 'democratizing, empowering promise of the mere presence of new media technology is far overstated' (p. 85). Brabham's argument is corroborated with early research which suggests that despite organisational innovations 'it does not appear […] that new technology leads to higher aggregate levels of political participation' (Bimber, as cited in Hindman, 2009, p. 10). The idea of citizen participation is predicated on a wide range of opinions and perspectives but using technology to merely increase the number of involved stakeholders does not guarantee diversity in views, particularly when the most vulnerable members of society often do not have access to capabilities of latest gadgetry (Brabham, 2008).

Cardullo and Kitchin (2017) claim that 'although smart technologies seek to promote engagement, they might deepen structural barriers to socio-political participation related to education, class, gender and ethnicity' (p. 14). It is therefore crucial that the future development of participatory technology considers the potential to exuberate digital dive which is increasingly gaining attention in both scientific and popular literature (Ertiö, 2015; Gabrys, 2014; Kleinhans et al., 2015; Norris, 2001). While more people are getting online every day, some research suggests that the skills needed to operate new technology effectively have perhaps even more stratifying effect than the access alone, potentially hindering widespread technologically-enabled citizen participation due to the inability of underprivileged citizens to operate latest tools and devices (Hindman, 2009; Norris, 2001).

2.2 Space for improvement

This paper argues that many of the shortcomings of the current participatory technologies stem from a lack of design aesthetic and interaction modalities that would make them appealing to citizens while simultaneously improving their accessibility and usability. Self-governance platforms are falling short on many aspects of contemporary best practices in the fields of human-computer interaction, user experience and user interface design. Numerous smart citizen initiatives take a form of limited experiments with a narrow scope and are often abandoned before they have time to mature and evolve into a useful tool. Most municipalities lack the domain expertise to develop a genuinely localised platform and therefore have to rely on faux-customised off-the-shelf solutions chosen from a growing array of competing offerings sold by a private sector. More often than not, citizen participation platforms used by local governments are over-engineered web portals that are only accessible from a desktop computer, are notoriously difficult to navigate, let alone use, and in the end, fail to engage anyone but the most eager and tech-savvy of citizens.

As indicated at the outset of the paper, the rapidly growing global population of smartphone users offers yet untapped potential for reinventing the citizen participation platforms around the principles of ubiquitous internet access and environment sensing capabilities embedded in mobile devices that we carry around everywhere we go. Due to its accessibility, responsiveness and simpler interaction modalities, mobile participation promises to engage previously alienated communities and is 'is expected to attract a much wider interest group than conventional participation tools, in particular youths and young adults who are difficult to engage in public affairs or participation schemes' (Kleinhans et al., 2015, p. 240).

Mobile participation stems from principles of co-creation that operates on the basis of crowdsourcing, or citizensourcing as it is sometimes referred to in the context of e-governance (Schmidthuber & Hilgers, 2018). Citizen sensing smartphone applications (apps) for capturing environmental data are sometimes subsumed under a category of mobile participatory platforms. However, there is a tendency in such systems to view citizens as mere environmental data points with no political capital and as 'ambient and malleable urban operators that are expressions of computer environments' (Gabrys, 2014, p. 42). This paper looks at a particular category of mobile participation referred to as m-participation which is explicitly about 'encouraging a continuous dialogue between a city and citizens by using contemporary technology' (Thiel, Fröhlich, & Sackl, 2016, p. 271).

Höffken and Streich (2013) define m-participation as 'the use of mobile devices […] via wireless communication technology to broaden the participation of citizens and other stakeholders by enabling them to connect with each other, generate and share information, comment and vote' (p. 206). According to Höffken and Streich (2013) the leading characteristics of m-participation are:

- multimodality of communication through different mediums such as voice, text, images, or video;

- in-situ communication that adds a component of spontaneity to an information exchange;

- unlimited real-time interaction around the world;

- smartphone are often deeply personal devices which are not shared with others;

- most people permanently carry their smartphones with them wherever they go;

- smartphones are switched on and readily accessible to use most of the time;

- additional costs for participation are low due to flat-rate charges for mobile internet access in many countries;

- mobile phones are ubiquitous in a sense that they can be taken anywhere, in both the public and private sphere.

The main advantage of m-participation over other forms of digitally-mediated participation methods is the portability, connectivity and ubiquity of the devices that 'eliminate spatial and temporal barriers' for participation-on-the-go by letting citizens 'pro-actively raise their voice' whenever and wherever they are (Thiel et al., 2016, p. 266). This enables governments and communities to make better decisions by tapping into local tacit knowledge through geo-tagged user input (Ertiö, 2015; Kleinhans et al., 2015). Korn (2013) uses a concept of situated engagement to describe in-situ participation that 'allows citizens to discuss public matters in their immediate proximity, at a time and place relevant to each personally' (Ertiö, 2015, p. 306).

M-participation brings with it its own set of thorny socio-political issues. Napoli and Obar (2014) conducted a comparative analysis of mobile-based internet access with desktop PC-based internet access and concluded that mobile access operates on less open and flexible platforms that offer lower levels of interface functionality, speed, memory and content availability which 'detrimentally affect users' abilities to engage in information seeking and content creation, and to develop a wide range of digital skills' (p. 330). This disparity in the capabilities of internet-enabled devices may result in the creation of mobile internet underclass further widening the digital divide (Ertiö, 2015; Napoli & Obar, 2014).

Despite the limitations described here, there is room for significant improvement in the space of m-participation. If done well, many of the shortcomings outlined in this subsection can be mitigated with sound design decisions, long-term iterative development and sustained collaboration between the citizens, professionals, academics and public sector; pushing the entire field towards more inclusive, responsive and citizen-centric modes of participation.

M-participation is only emerging as a stand-alone field of study. Majority of the existing research into digitally-mediated citizen participation subsumes m-participation under an umbrella term of e-participation. While m-participation is the primary focus of the research presented here, both terms are used throughout the paper depending on which was deemed the most appropriate for a given context.

The remainder of the paper focuses on developing a set of design heuristics for developing modern m-participation platforms based on a research methodology presented in the next section.

3. Methodology

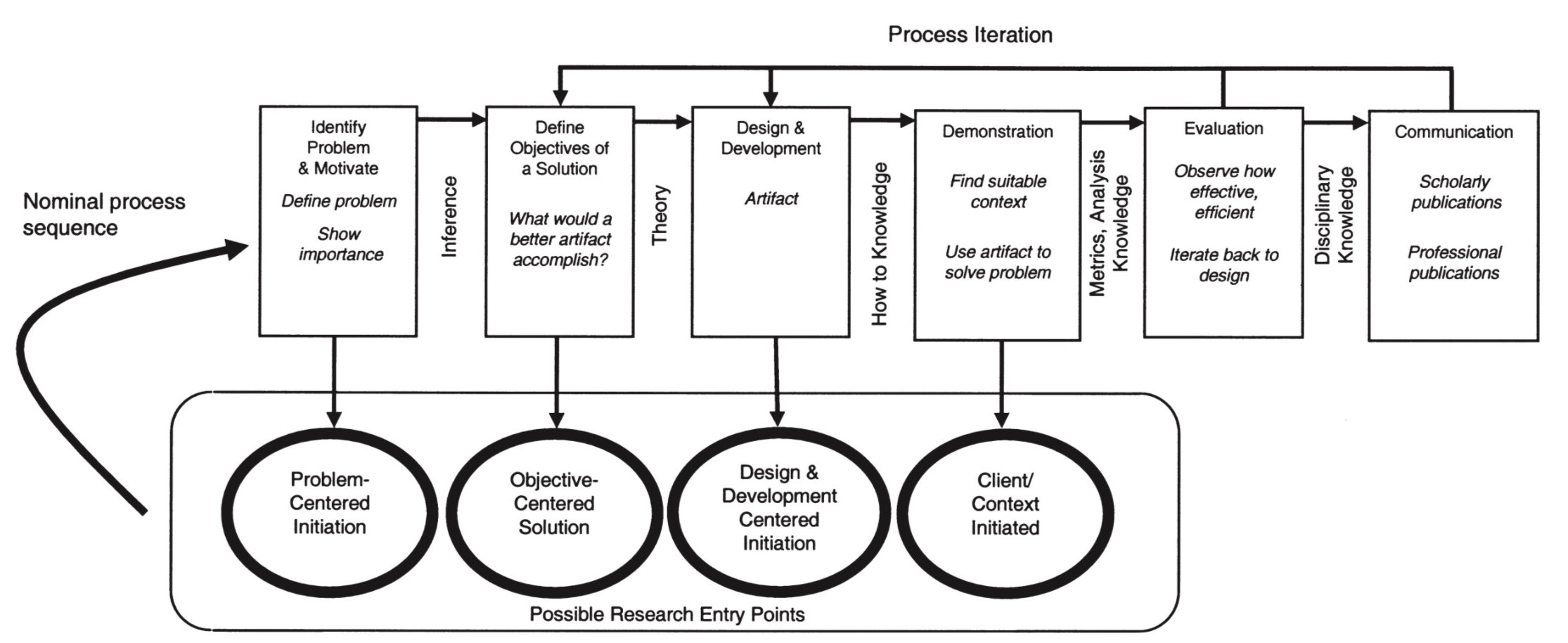

The research presented here does not lend itself to traditional research methodologies due to its pragmatic nature and its focus on actionable outcomes. To that end a widely cited Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) as proposed by Peffers et al. (2007) is applied to assist in the creation of design heuristics for participatory platforms and a subsequent platform prototype. DSRM is a design science methodology that 'attempts to create things that serve human purposes' rather than to objectify reality (Peffers et al., 2007, p. 48). This methodology is specifically aimed at design and development of information system and at its core is a production of an artefact that address an observed problem. The DSRM process model is comprised of the following six successive activities:

Activity 1: Problem identification and motivation. Define the research problem and justify the value of developing a solution to it. This activity includes evaluating existing solutions to an identified problem.

Activity 2: Define the objectives for a solution. Infer objectives of the information system based on the problem definition and knowledge of what is currently possible and feasible. Objectives can be either quantitative or qualitative such as a 'description of how a new artifact is expected to support solutions to problems not hitherto addressed' (Peffers et al., 2007, p. 55). These objectives are used to assess the appropriateness of the artefact.

Activity 3: Design and development. Determine desired characteristics, functionality and architecture of the artefact and then create it. Artefacts can take a form of constructs, methods, models or instantiations that are broadly conceptualised as 'any designed object in which a research contribution is embedded in the design' (Peffers et al., 2007, p. 55).

Activity 4: Demonstration. 'Demonstrate the use of the artifact to solve one or more instances of the problem' through an experiment, simulation, case study or other appropriate activity (Peffers et al., 2007, p. 55).

Activity 5: Evaluation. 'Observe and measure how well the artifact supports a solution to the problem' (Peffers et al., 2007, p. 56). This activity comprises of comparing the objectives defined in activity 3 to the actual performance of the artefact based on the demonstration. Conceptually, the evaluation can include 'any appropriate empirical evidence or logical proof' (Peffers et al., 2007, p. 56). As a result of the evaluation, the researcher can decide whether to iterate back to one of the previous steps or continue to the last activity to communicate the results and leave further improvements for future projects.

Activity 6: Communication. Diffuse the knowledge gained from the research. The purpose of this activity is to communicate the importance of the problem and the utility and effectiveness of the artefact to the relevant audiences.

While the activities in the process model are depicted sequentially, research can be initiated at any step in the process. Figure 2 shows the process model illustrating the different stages of DSRM together with various entry points for research.

Figure 2 - DSRM Process Model (Peffers et al., 2017, p. 54)

3.1 Applying the DSRM process model

This paper focuses primarily on the first three activities of the DSRM process model. The remaining three are addressed peripherally since they part of an ongoing effort to develop a participatory platform. The research takes a problem-centred approach and therefore starts with the activity 1 followed by the remaining steps in a successive order. Following is an outline of each of the activities of the DSRM process model within the context of the current research:

Activity 1: Problem identification and motivation. First a review of existing e- is presented, followed by a more detailed design analysis of two selected platform which were chosen based on rationale presented later in this section. Then shortcomings of current solutions are summarised followed by an articulation of the problems that highlighting the key areas that need improvement. Motivation draws on the introduction and the overview of participatory approaches to smart cities presented earlier.

Activity 2: Define the objectives for a solution. The analysis of current solutions in combination with primary data is used to develop a set of guiding principles for design of participatory platforms. The outcome of this activity are design heuristics for participatory platforms which are then used to inform the design of an artefact which in this case takes a form of an interactive visual prototype. The design heuristics serve a dual purpose; first as a set of criteria against which to assess the prototype and second as an artefact in its own right that can be used by researchers, governments, citizens and other parties to develop participatory platforms.

Activity 3: Design and development. A prototype is developed based on the design heuristics established in the previous step. The prototype is comprised of high-fidelity mock-ups of a smartphone user interface for a proposed participatory platform that were produced using Sketch software and linked together to mimic interactions using InVision prototyping service. The chief purpose of the prototype is to illustrate some of the design heuristics, rather than provide an illusion of a fully functioning smartphone app.

Activity 4: Demonstration. The prototype produced in the previous step was tested with a group of potential users and their feedback was collected.

Activity 5: Evaluation. The evaluation is conducted by assessing to what degree do the features of the prototype align with the design heuristics that serve as success criteria. The evaluation is complimented with the user feedback obtained in the previous step.

Activity 6: Communication. The research purpose and motivation are presented on a publicly accessible website that showcases the proposed participatory platform and invites visitors to participate in the further development of the platform.

3.2 Selected platforms

As alluded in the previous subsection, the two platforms selected for the detailed analysis of the current participatory platforms are CONSUL and UrbanLab. CONSUL has been selected for its large global user base, extensive feature set, advanced participatory mechanisms, open-sourced codebase and an ambitious vision to become a go-to participatory platform for cities around the world. UrbanLab was chosen due to its design aesthetic that is closest to the current trends in the design of digital interfaces from all the platforms that were considered. Furthermore, since it is a paid product it was deemed suitable for comparison with CONSUL.

3.3 Collected data

The primary data for the research was collected through online surveys and informal online discussions with people that have tested the prototype. An online survey was produced using the Typeform data collection tool to validate some of the design heuristics and core mechanisms of the proposed platform. The survey was circulated using social media and it used a logic jump feature to ask participants additional probing questions based on their previous answers. The survey was completed by 25 respondents from 13 cities, with London, Copenhagen, Prague most represented.

For user testing, a link to an interactive prototype was sent to selected people in the author's network together with a link to an online form with open-ended questions and opinion scales. A follow up chat-based discussion was held with each of the participants. The prototype was tested this way with a total of 3 participants.

In addition to aforementioned surveys and discussion, one informal interview was conducted with a staff member of Barking and Dagenham borough council in London, United Kingdom. The author followed up with the council several times in an attempt to arrange another more focused interview, but did not receive any response despite the initial enthusiasm to participate in the research. Nevertheless, the single interview provided some insight into certain aspects of citizen participation from a municipal perspective.

4. Review of existing solutions

Studies suggest that citizens are keen to use social media tools to engage with planners and local governments (Evans-Cowley & Hollander, 2010; Kleinhans et al., 2015; Williamson & Parolin, 2012). These findings reflect the experience of Barking a Dagenham whose citizens are actively engaging with the council through the borough's Facebook page. However, despite the citizen activity, governments 'have not yet been able to tap effectively into citizens' online social networking practices that are part of citizens' daily routines' (Kleinhans et al., 2015, p. 241). For any m-participation platform to be successful, it has to effectively engage citizens using contemporary communication modalities enabled by ubiquitous real-time information exchange via smartphones. This section identifies problematic aspects of current participatory platforms, with a particular focus on m-participation, by looking at the existing research and by conducting an exploratory.

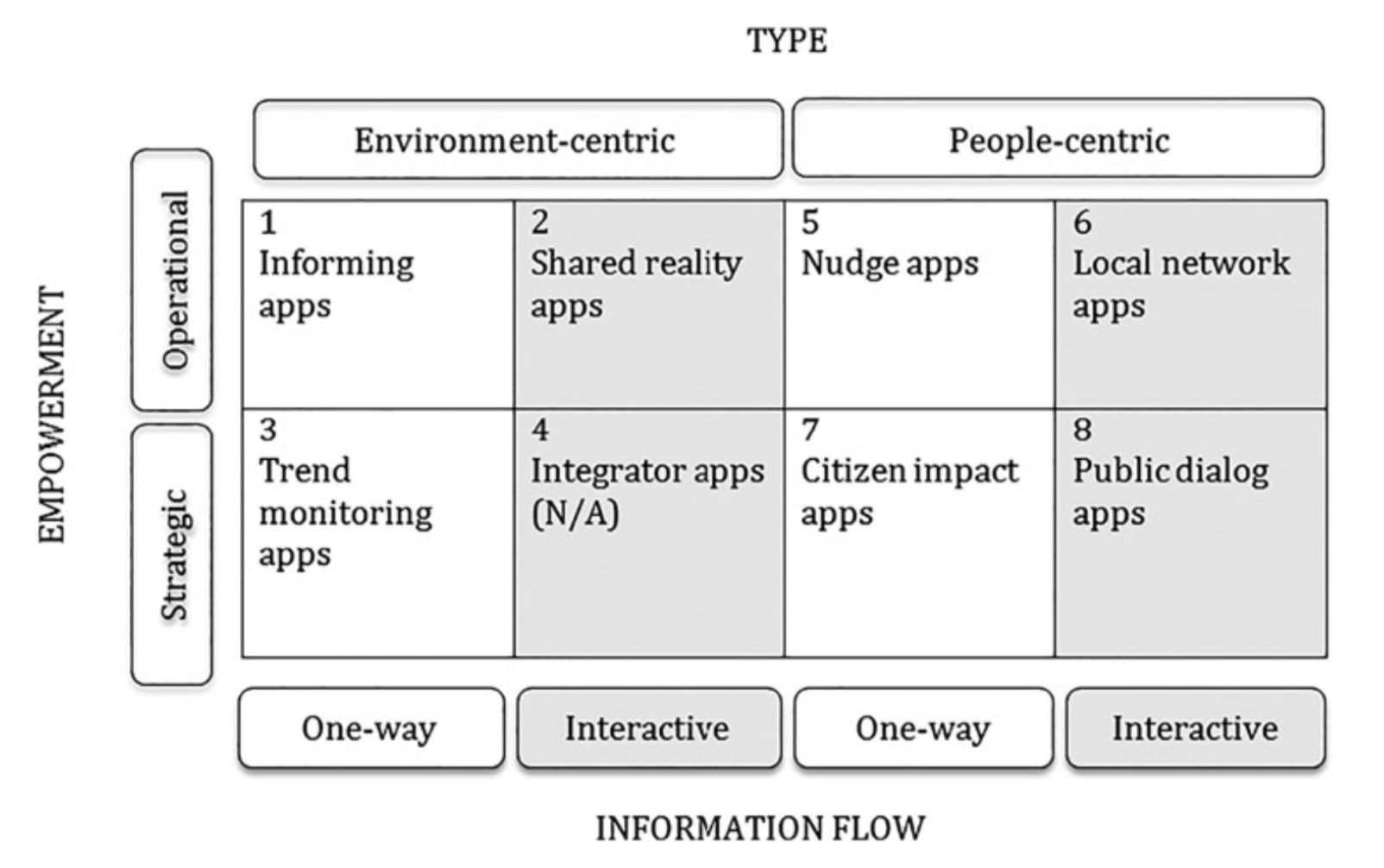

M-participation is often subsumed under e-participation and has got little attention from researchers as a stand-alone field of study. One of the most extensive investigations specifically focusing on m-participation has been conducted by Ertiö (2015) who has identified approximately one hundred urban governance smartphone apps, 35 of which were selected for a sample that was used to develop a typology of participatory apps. The typology uses three dimensions of participation to categorise m-participation apps as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 - Typology of Participatory apps (Ertiö, 2015, p. 311)

One of the most prominent examples of a successful m-participation initiative is the FixMyStreet platform developed by a UK-based non-profit MySociety. At the time of this writing, people have reported over 1.3 million problems from categories such as highways, potholes or flytipping using the FixMyStreet smartphone app; over 500 thousand of those problems were marked as fixed by local councils throughout the UK ('FixMyStreet', 2018). The platform has been running since 2007, which explains the relatively high numbers of reported issues. The author would argue that FixMyStreet is probably the most widely recognised and successful m-participation platform available today.

Using Ertiö's typology of participatory apps, FixMyStreet is a typical example of an informing app which citizens can use to report environmental data to their local government. According to Ertiö (2015) informing apps comprise the largest category of m-participation solutions available. Ertiö's findings are corroborated by an earlier study from Tambouris et al. (2007) that looked at 20 e-participation projects and concluded that the commonly used e-participation platforms mostly focus on reporting and issue management. Ertiö goes on to conclude that only 'a few apps have a citizen-centric design and focus on substantial matters such as infrastructure, public spaces, or sustainability issues' and that there is 'still little evidence of sustained dialogue between local governments and citizens through mobile-based services' (2015, p. 316).

Existing research shows that local governments predominantly apply one-way 'push' strategy for developing participatory ICT solutions (Buccoliero & Bellio, 2010; Kleinhans et al., 2015; Mergel, 2013; Welch, Hinnant, & Moon, 2005). Solutions built primarily around the principles of one-directional information flows and the needs of governments are 'modulated on structures and organisational responsibilities instead of on the needs and on the demand of citizens' empowerment' (Buccoliero & Bellio, 2010, p. 236). Cardullo and Kitchin (2017) argue that 'in cases where participation and co-creation are initiated by those in power, rather than from bottom-up by citizens themselves, the ideals of shared or citizen-dominated decision-making […] are rarely present' (p. 16). Therefore, conceiving participatory initiatives around legacy bureaucratic structures of governmental organisations is unlikely to produce solutions that would be widely adopted by citizens.

This paper focuses on interactive people-centric public dialogue apps as indicated in Ertiö's typology. Solutions in this category are based on bi-directional information flows, continuous feedback, responsive dialogue and mutual discourse that promote a genuine discussion between local government and its constituents (Williamson & Parolin, 2012). Additionally, they can also support rich interactions and deliberation between citizens (Ertiö, 2015).

The following subsection takes a closer look at two specific solutions that provide a two-way interactive platform where citizens can mutually deliberate and discuss with direct input from their local government.

4.1 Analyses of selected platforms

CONSUL

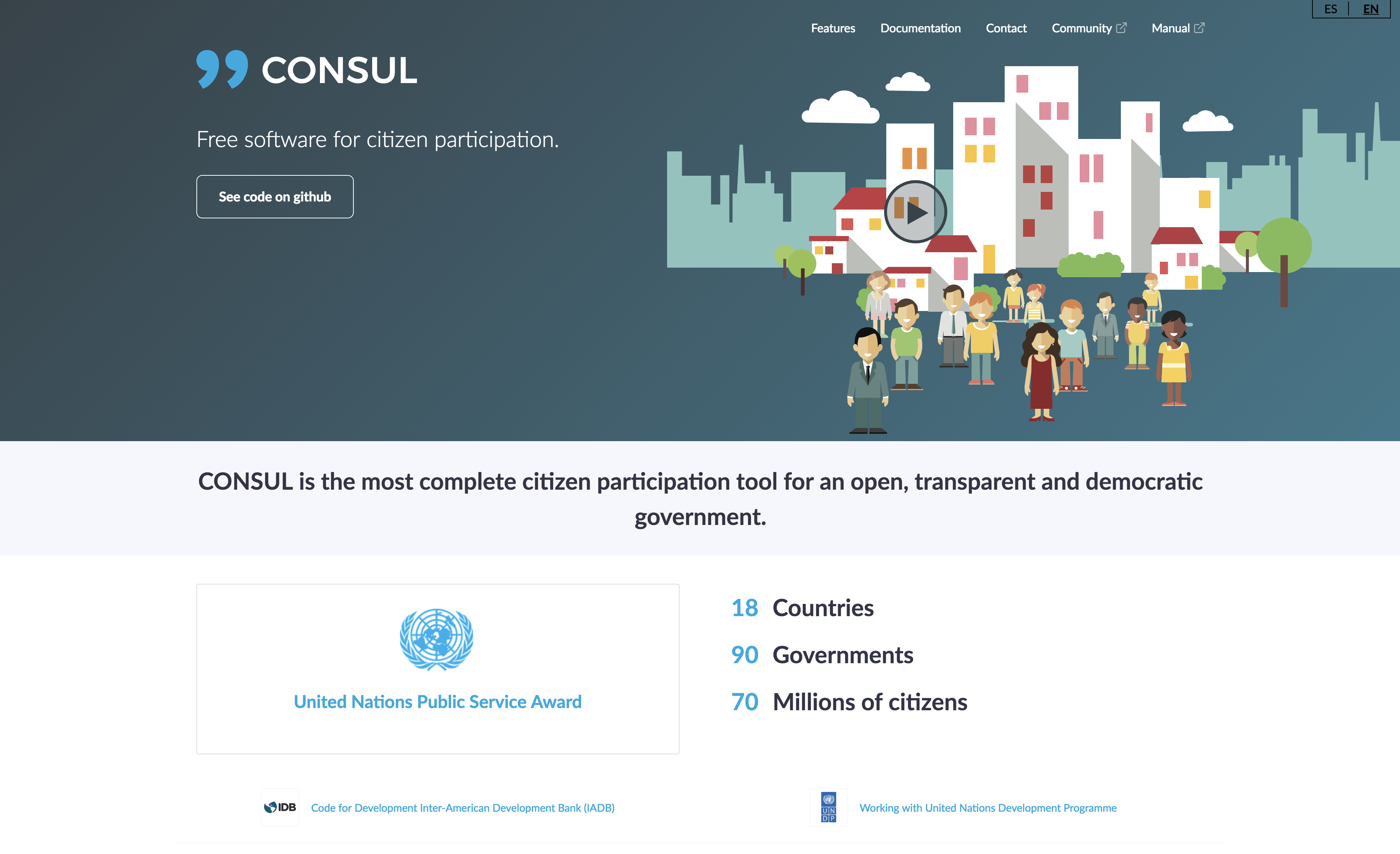

CONSUL is an open-source citizen participation platform initially developed for the Madrid government e-participation website in 2015. They describe their solution as the 'most complete citizen participation tool for an open, transparent and democratic government' ('CONSUL', n.d.). According to the website, the platform is used by 90 governments and 70 million users in 18 countries. The website does not disclose if the user count represents an actual number of users, or whether it denotes a potential reach based on the population of the cities where CONSUL is being used. It is doubtful that there are 70 million people actively participating on the platform. Nevertheless, CONSUL seems to be the most widely deployed public dialogue platform in the world. A screenshot of the platform's promotional website is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 - Screenshot of CONSUL's promotional website. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from http://consulproject.org/. Screenshot by author.

Labels and call to actions on the website highlight the open-source nature of the project by encouraging visitors to read the documentation and explore the code base on GitHub. CONSUL builds trust and asserts legitimacy by prominently showing the logo of United Nations and informing visitors that the platform has won the United Nations Public Service Award. The website also shows a map of the cities that are using CONSUL as well as a grid of logos of municipalities which are linking directly to the platform instance of the given local government. It seems that the majority of the cities that are using CONSUL are from Spanish-speaking countries, predominantly Spain and South America, presumably due to the Spanish origin of the platform.

CONSUL's main GitHub repository has been favorited 648 times, and 83 people have contributed to it at the time of this writing; by far the highest numbers of any open source participatory platform that the author investigated, most of which have been favorited a maximum of few dozen times and contributed to by a handful of people. From the promotional material available online it is clear that the principal feature of the platform is the fact that it is fully open-sourced and therefore any municipality or even a citizen can download CONSUL, customise it exactly to their needs and make it accessible online for anyone to use.

To explore the core concepts and functionality of the platform, the author has signed up and tested a CONSUL platform used in Madrid. At first sight, the visitor is presented with a wide variety of menus, subsections and labels that are all competing for the viewer's attention. To someone who has just registered on the platform, the interface gives an impression of an intricate tool with many possibilities which requires a relatively high initial time investment in order to learn how to navigate it and use it effectively. The platform offers useful tips that are conveniently placed throughout the interface to help the first-time users grapple with some of the mechanisms and concepts, to compensate for the seemingly complicated structure. Figure 5 shows a screenshot of the 'Proposals' section of the platform.

Figure 5 - Screenshot of a 'Proposals' section of CONSUL platform. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from https://decide.madrid.es/proposals. Screenshot by author.

The language and micro-copy (Babich, 2016) used throughout the CONSUL's interface accentuate the open-source spirit of the project. The friendly and humane tone makes the platform appear approachable and well-intentioned which may help put citizens at ease with using CONSUL to comment and share opinions. Furthermore, the user interface controls are available in multiple languages by default, making the site more accessible and usable to different groups. One of the most prominent features is the ability of citizens to freely tag debates and proposals with a text of their own choosing. The entirely open-ended citizen-generated folksonomies (Rosenfeld, Morville, & Arango, 2015) exemplify a genuinely bottom-up approach that lets the platform to be thematically structured around the emergent needs and concerns of citizens. Figure 6 shows a screenshot of the interface for creating a new debase which illustrates some of the citizen-centric mechanisms embed in the platform.

Figure 6 - A screenshot of an input form for creating a new debate on the CONSUL platform. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from https://decide.madrid.es/debates/new. Screenshot by author.

The platform's main weakness is its visual presentation and content hierarchy that given an impression of an institutional website with a rather dull and uninspiring aesthetic. In combination with relatively complex information architecture, the platform's initial appearance might deter a significant portion of casual users. This observation seems to be reflected by the relatively low number of active users on the CONSUL platform operated by the city of Madrid.

Looking at some of the older data on the platform, there seem to have been a few temporal bursts in participation for certain proposals that can probably be attributed to campaigning and promotion outside of the platform. In the last two years in Madrid, there were a total of ten proposals that gained more than 1000 supporters. Majority of proposals have only a handful or no supporters with no substantive activity. The number of citizens participating in the 'Debates' section of the platform seems to be slightly higher than for proposals, but they are still exceptionally low for a city with over 3 million inhabitants. A brief investigation showed that the CONSUL platform fails to engage a significant portion of the population in other cities as well.

Overall, CONSUL is an exceptionally well developed and mature citizen participation platform founded on citizen-centric ideals of empowerment and deliberation. The solution seems to stress the role of a citizen and their input over that of a government, which is a rare sight for a platform of this scale and reach. However, the platform's usability is negatively affected by an overly complicated and over-engineered information architecture which is undermining the CONSUL's potential to reach a wider audience.

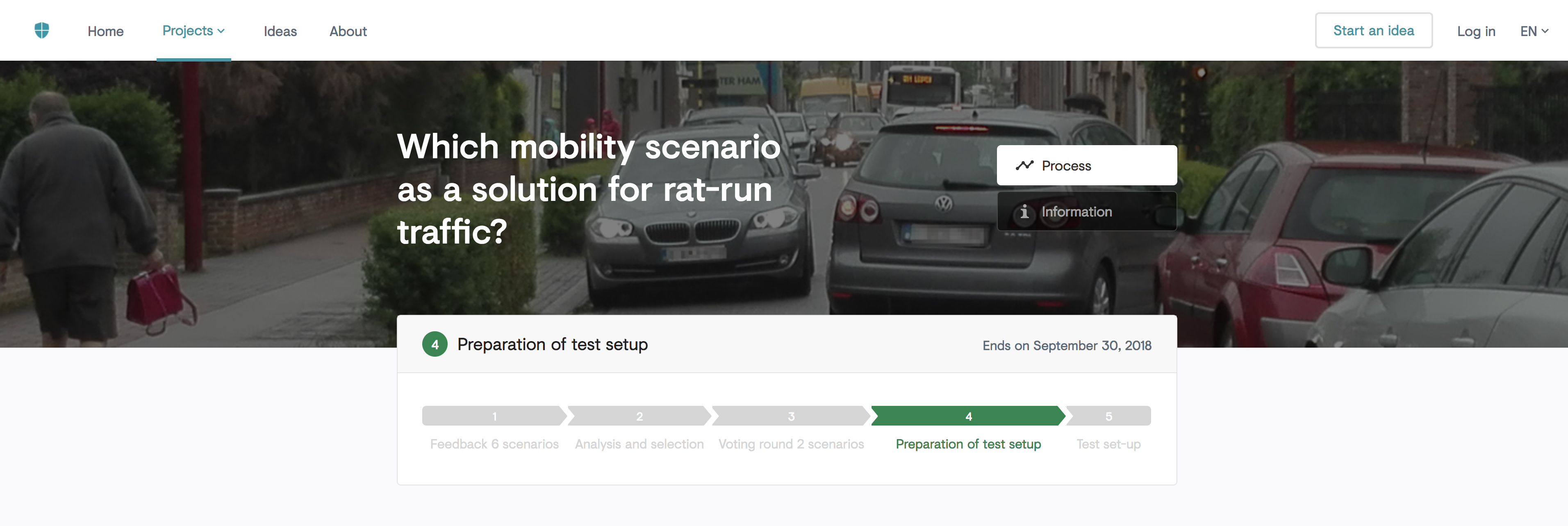

CitizenLab

CitizenLab is a Brussel-based civic technology startup founded in 2015 by two former students that have started the project during their university studies (Mihailescu, 2018). The company brands itself as a 'ready-to-use citizen participation platform for local governments' and according to their website 75 governments and 25.000 citizens are using the platform ('CitizenLab', n.d.).

Figure 7 - Screenshot of CitizenLab's promotional website. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from https://www.citizenlab.co. Screenshot by author.

The CitizenLab's promotional website, shown in Figure 7, immediately invokes a sense of professionalism and seriousness through a clean and elegant visual aesthetic typical of many software-as-a-service companies today. This perception is further stressed by a prominent placement of logos of brands such as Forbes and Gartner with a strong orientation towards a business-minded audience. The logos further serve to establish an immediate sense of trust and legitimacy.

According to the website, the platform utilises a three-step process of 'Engage', 'Manage' and 'Decide' that promises to 'centralise all citizens interactions with an all-in-one platform' ('CitizenLab', n.d.). This somewhat paternalistic top-down tone seems to fit the business-oriented strategy of CitizenLab which is promoting their solution together with accompanying implementation, maintenance and training services to governments around the world.

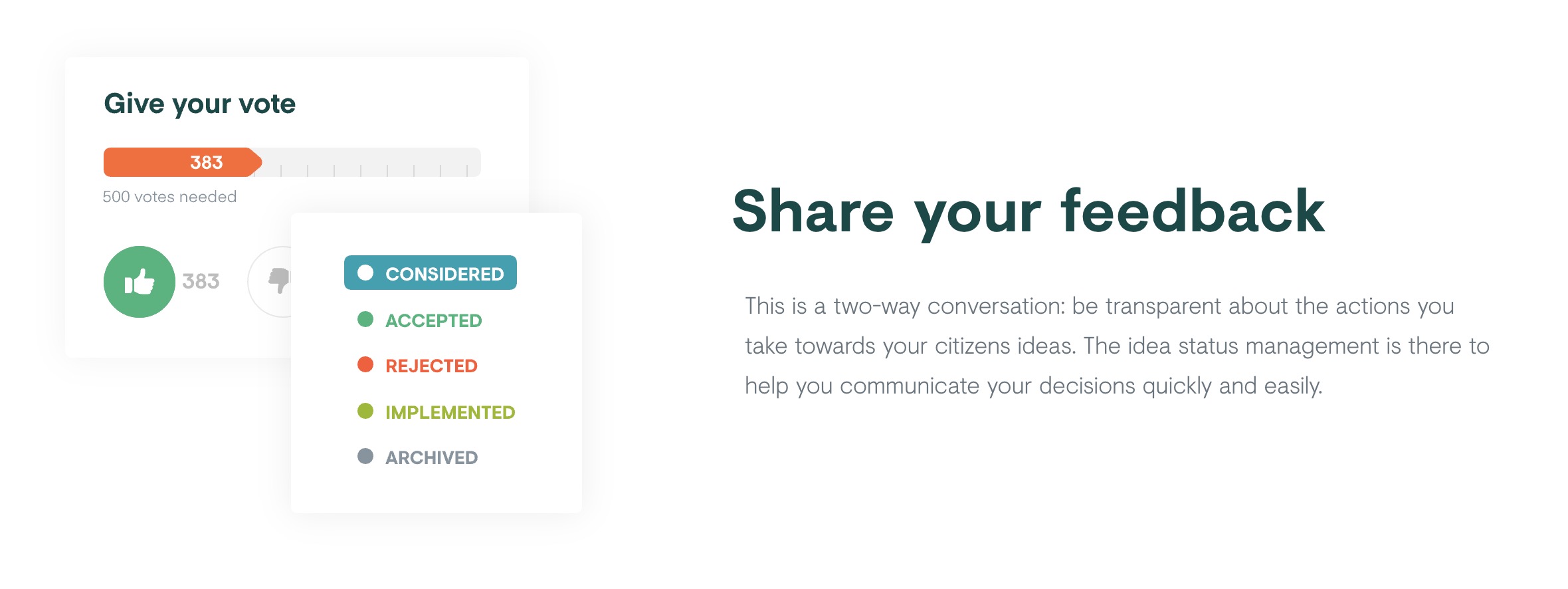

The author was able to obtain access to an example version of CitizenLab platform, intended for demonstration purposes, that was used to gauge the basic principles and mechanisms operating on the platform. The platform has a uniform card-based user interfaces with elements familiar from other social media platforms, such as like/dislike buttons and comments. CitizenLab's information architecture is organised around a relatively small number of thematic projects which are initiated by a local government. Citizens can then propose and deliberate ideas by attaching them to a specific project. shows a screenshot of the 'Ideas' section of the platform.

Figure 8 - Screenshot of the 'Ideas' section of the platform. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from personal communication. Screenshot by author.

CitizenLab's strongest suit is its information architecture that is easy to navigate and comprehend and is further complemented with a clear and visually appealing design aesthetic. Subtle and easily digestible visual cues inform citizens about the progression of a project (Figure 9) and what actions is the local government taking on ideas being posted on the platform (Figure 10). This gives the platform a sense of responsiveness and immediacy that most other participatory solutions fail to elicit.

Figure 9 - Screenshot of a page indicating the progression of a project. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from personal communication. Screenshot by author.

Figure 10 - Screenshot from CitizenLab's promotional website with a preview of different actions governments can take on the citizen-submitted ideas. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from https://www.citizenlab.co/. Screenshot by author.

It can be argued that the platform takes a government-centred approach to citizen participation due to the fact the ideas from the citizens are constrained at the level of projects which are initiated by a local government. It would be possible to have a catch-all project labelled 'Other' but the information architecture of CitizenLab implies a primacy of a project over an idea. This observation implies that the thematic clusters that are produced on the platform over time are ultimately dictated from the top-down by the government, rather than from bottom-up through an organic emergence of themes and concerns from citizens.

Overall, CitizenLab is a breath of fresh air in the field populated mostly with well-meaning but poorly designed solutions. The platform provides smooth user experience and a frictionless onboarding process that are critical for engaging different demographics that would otherwise not be willing to invest time in learning to operate a new tool. Since the author only had access to a demo version of the platform populated with fake data, it could not be determined to what degree do the aforementioned design qualities translate into citizen activity and adoption rates in cities using CitizenLab's solution.

Summary and comparison of the two platforms

The public presentations of both CONSUL and CitizenLab seem to be aimed at governments, with little or no guidance on how to establish or initiate a platform as a citizen. The government-oriented rhetoric evident in the promotional materials of both platforms indicates a bias towards viewing governmental organisations as a primary target group for conceiving and initiating participatory projects. These findings are corroborated by the conclusions of other researches presented earlier.

Both platforms rely on a web browser as their primary access point with the user interface optimised primarily for desktop use. While both websites use responsive design to cater to different screen sizes, like mobile phones or tables, there are no stand-alone native apps that users can download to their phones. As a consequence, platforms cannot effectively utilise some of the sensors embedded in mobile devices, such as precise GPS position or direct camera access, that could significantly improve platforms' capacity to provide media-rich and hyper-local experience. Furthermore, not having direct and convenient access to a platform through a permanent placement of an icon on the user's smartphone home-screen means that citizens are less likely to casually interact with the platform on an in-situ basis.

Of the two platforms, CitizenLab performs better in terms of design aesthetic and ease of use, but its managerial rhetoric, proprietary solution and commercial motives might not fare well when set in a broader socio-political context of contemporary smart city narrative. The inability to freely tinker and customise the solution without the company's permission may present a significant barrier for many cities, if they can afford the cost of licensing and servicing the platform in the first place. In that regard, CONSUL is built with notably more open and egalitarian principles at the core of the platform but would benefit from a more streamlined design direction and simpler information architecture that would make the platform more accessible to casual users.

Despite their shortcomings, both CONSUL and CitizenLab show a great promise and present a substantial improvement over the majority of current solutions available to citizens and governments around the world. The vital features that are currently missing from both platforms are a support for geolocated citizen input and a better alignment with the real-time communication and interaction modalities permitted by an increasingly ubiquitous access to smartphone technology. A lack of these features is typical of a majority of public dialogue and deliberation platforms available today, and the author expects the number of solutions which support them to grow in the coming years.

4.2 Survey findings

All of the respondents who indicated that they access government digital services, do so using a web browser on a desktop computer or a laptop. About 40% of those respondents also access the services using either a native smartphone app or a web browser on the phone. They primarily use the digital services to fill out and submit paperwork or to search for relevant information. A single respondent indicated that they use the tool to suggest improvements to their local neighbourhood. Respondents who do not use government digital services indicated that they do so because they prefer face-to-face contact or that there are no digital government services available in the area where they live.

Respondents were invited to elaborate on the details of how they use the digital services, as well as comment on what features they find most useful and what aspects of the service(s) would they change or improve using open-ended text fields. Respondents use digital services to perform many of the tasks that previously had to be done by visiting a government facility, such as submitting printed copies of documents, booking appointments or filling out tax reports. Respondents mentioned the benefits of going paperless and not having to be physically present when dealing with the government, giving them more flexibility and saving them time. Half of the respondents from this logical section of the survey mentioned user-friendliness as a significant drawback of digital services they use. Some mention that they find it hard to navigate the service and that information can be difficult to find as it is sometimes spread across different services. Three respondents expressed concerns over the usability and accessibility of the user interface for particular groups such as older adults and people with disabilities. Second most frequently mentioned drawback was that the services were poorly optimised to the use on mobile phones. Several respondents also mentioned they would appreciate if the service was available in more languages.

The results of the survey suggest that people are happy to use digital services to perform or replace, tasks that previously had to be done in person. However, there were no mentions or indications of any form of interactive communication that would resemble a dialogue between the respondents and the government. Overall, the findings from the survey support the conclusions from existing researcher.

4.3 Problem identification

This subsection utilises the DSRM Process Model approach to pose some of the key findings from the current e-participation landscape as problems to be addressed later using design heuristics for participatory mobile spaces. The problem statements draw on the literature review, analyses of two prominent participatory platforms and survey results presented earlier. The problems have been articulated as follows:

Existing e-participation solutions are imposed from the top-down by governments not initiated from the bottom-up by citizens.

Existing e-participation solutions are devised around the organisational structures and motivations of governments, not around the needs and concerns of citizens.

Existing e-participation solutions lack visual aesthetics and interaction modalities that citizens are familiar with from other digital products.

Existing e-participation solutions do not support localised citizen deliberation through geolocated user-input.

Existing e-participation solutions do not engage a substantial nor representative portion of a population.

The next section presents the design heuristics that address the problems identified here.

5. Design Heuristics for Mobile Participation Spaces

This section presents the Design Heuristics for Mobile Participation Spaces developed as a heuristic tool to address some of the foundational conceptual and pragmatic challenges currently facing the field of digitally-mediated citizen participation systems. As reiterated throughout this paper, the focus is on creating solutions that aim to support and improve deliberation between citizens and facilitate 'instant, location-based interaction between individual members of civil society and urban planning administrators and politicians' (Schröder, 2014, p. 76).

The heuristics provide design objectives for citizen participation solutions that address the problems identified in the previous section, as part of the DSRM Process Model approach. They are meant to be used by researchers, designers, software developers, businesses, governments, citizens and any other individuals or organisations as a conceptual and strategic framework for creating and evaluating participatory information systems.

The Design Heuristics for Mobile Participation Spaces take a form of high-level abstractions and deliberately use broad terminology as not to limit their applicability to a particular setting or technology which inherently change over time. In the context of the research presented here, m-participation is used to illustrate the utility of the design heuristics. However, the heuristic framework presented here is conceived as a generalisable set of principles, guidelines and best-practices that embody the ideals and values of collaboration, co-creation and collective flourishing. The establishment of such heuristics represents a first step towards the creation of novel models of citizen participation based on principles of mobility, ubiquity, inclusivity, and distributed decision-making and deliberation through digitally-mediated information spaces.

Citizen-first system design

A citizen-first information system is designed and developed with citizens as a principal target group, rather than government as is usually the case today. Such a system aims to reverse the top-down power dynamic, in which governments impose technological solutions on its constituents, and instead empowers citizens to initiate a take control over the system's structure and modalities of interaction. A shift from government-first to a citizen-first paradigm lets citizens exert pressure over their representatives and hold them liable through the power of collective deliberation. While a municipal buy-in is a vital component of a prosperous citizen participation initiative, the citizens should have the right and the ability to decide on the common course of action based on a localised consensus, with or without the consent of the government.

This not be confounded with citizen-centred rhetoric that is increasingly used in corporate storytelling to make smart city products appear more inclusive and palatable to the public. A solution can presumably be developed around citizens, but not necessarily prioritise their agency and needs.

Inclusive, accessible and open

A genuinely inclusive, accessible and open solution provides a neutral space for dialogue, deliberation and decision-making for everyone irrespective of their age, race, gender or physical ability. The platform should, therefore, be accessible from a range of devices and interfaces, such as smartphone apps, responsive websites, digital kiosks embedded in the built environment, text messages, telephone calls or in-person visits to a local facility. The platform interface should also be available in a multitude of languages based on a local demographic; this is particularly important for growing metropolitan areas with a continuous influx of citizens coming from all over the world.

Different access points can vary in regards to interaction modalities and media-richness they offer, however, they all need to provide citizens with an equal decision-making potential and ensure that a minimum-viable version of the platform is always available to every citizen. Assistance, support and educational services should be available for citizens a communities that lack the necessary skills or resources to effectively operate within the platform.

Physical digitality

Transforming digital interactions into embodied interactions is a key for turning deliberation into concrete action. In order to elicit trust, support, and good-will of their constituents, governments need to ensure that the ideas, desires and concerns expressed in the digital space of a participatory platform ultimately materialise in the physical reality of citizens, either as a desired change to the built environment, a social gathering or a policy change.

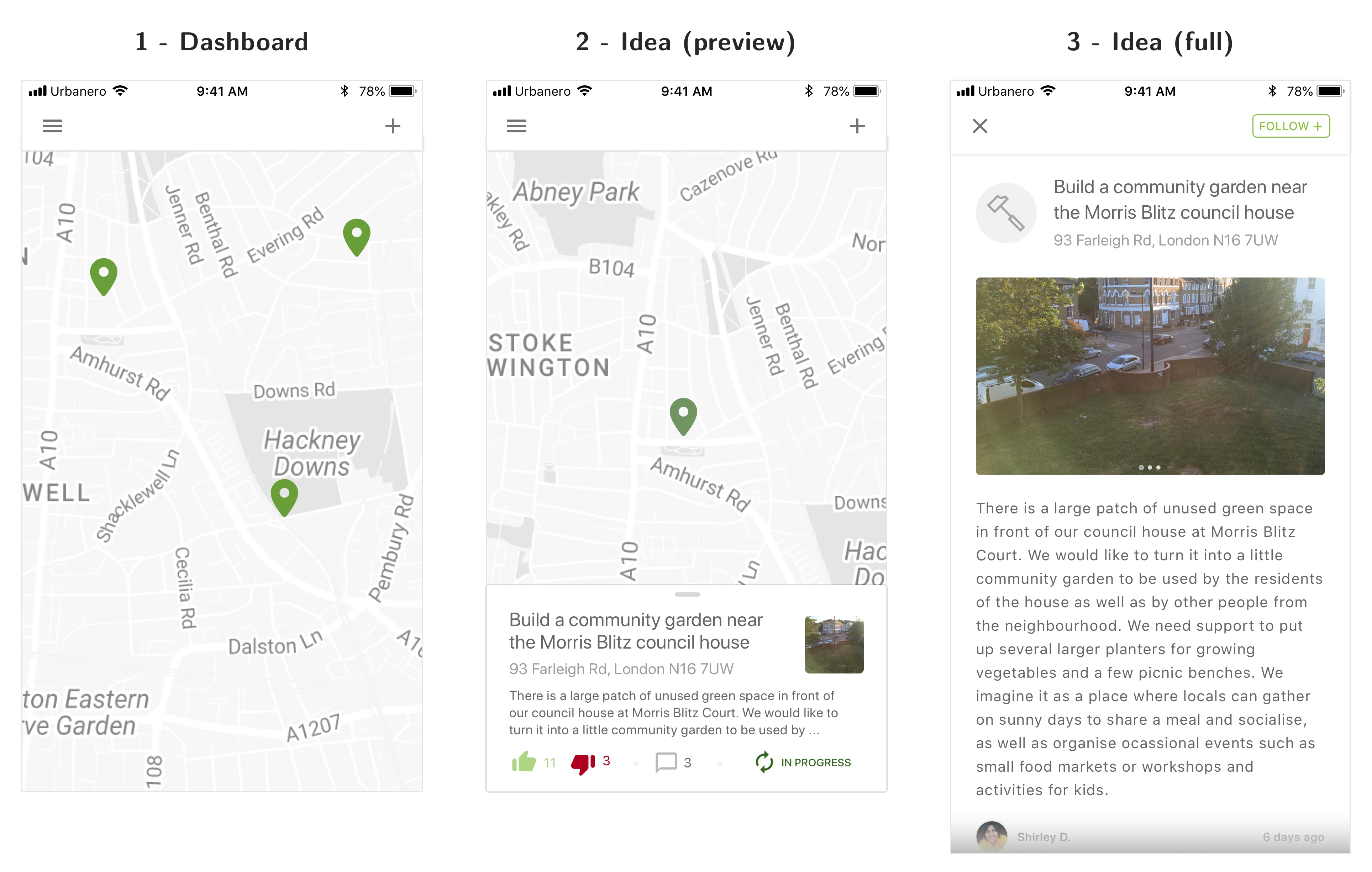

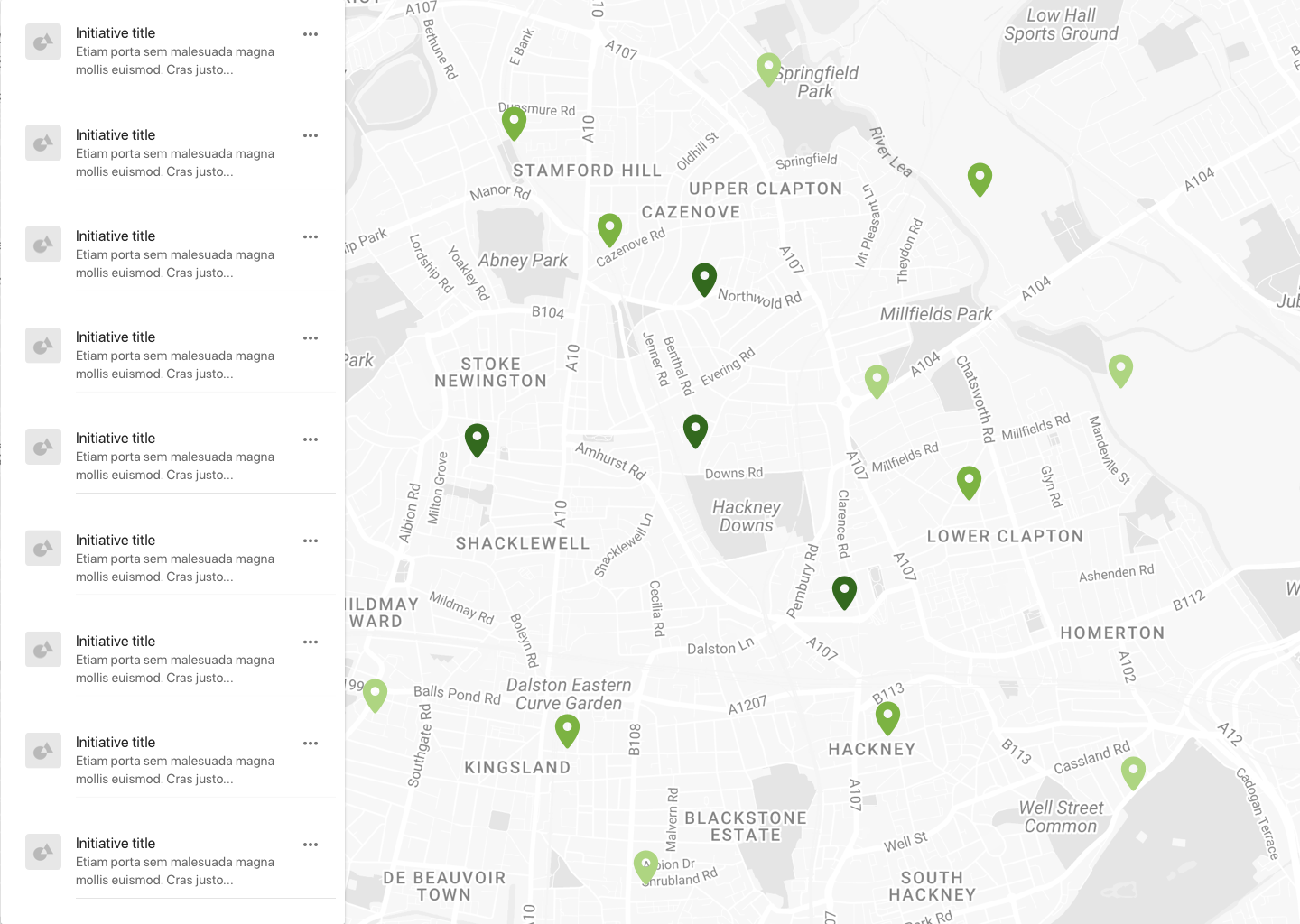

6. Platform concept presentation

This section presents a concept for a participatory solution based on the Design Heuristics for Mobile Participation Spaces. An interactive prototype of a smartphone app was used as a primary artefact for validating some of the assumptions and ideas developed in this research. Figure 11 shows a preview of different view types that were designed for the purposes of user testing.

Figure 11 - Screenshots of different interface views from the prototype. Author's own production.

The primary interface of the platform is a map showing a portion of an area or neighbourhood based on the user's current location. Citizens can add ideas, suggestions and reports to the platform by placing a pin on the map in their immediate surroundings. Each idea contains a title, description and optionally an accompanying image(s). Users can see ideas added by others within a certain radius of their current location, as well as upvote, downvote and comment on them. When a user clicks on a pin a corresponding idea is shown in the form of a card preview. Once the user clicks on the preview, they are presented with a full card containing all the information and activity related to that idea.

Figure 12 - Screenshot of a part of the screen showing a sample response from a local authority. Author's own production

The citizen-first structure of the platform emerges organically through contributions from the citizens. Figure 12 shows a partial screenshot from a card view of the prototype which shows which local authority is responsible for action on a given idea and the status which indicates the progress or decisions being made on a given idea. This seemingly smart component of the user interface constitutes a key mechanism of the platform. In a scenario where a local government refuses to interact with their constituents using the platform, it could still serve as a powerful public opinion amplifier that enables citizens to see how many people share similar sentiments. If an idea reaches a critical mass of supporters, it can generate political momentum and media coverage that directly exerts pressure on a local administration to act on an idea.

Figure 13 - Basic wireframe suggesting a potential design direction of a municipal dashboard for interacting with citizens. Author's own production.

6.1 User testing and evaluation

Respondents were most concerned that the government would not respond to ideas and issues posted on the platform. They also expressed doubts whether enough people would use the platform for it to be active enough to create a critical mass of users that would make solution viable on a larger scale.

6.2 Communicating the findings

A project homepage was developed and published at https://urbanero.org/ to communicate the motivation and rationale behind the research and the platform concept to the public. A GitHub page was also set up for the platform inviting people to contribute and to reach out to the author with ideas and feedback. The domain name extension .org and the GitHub page are meant to convey the open-source nature of the project.

7. Discussion

At the core of the proposed Urbanero platform is a premise that citizens can immediately see who is responsible for taking action on their ideas. Technically, this solution relies on fine-grained data that would allow the platform to instantly identify a local administrative body that is responsible for any given location based on the coordinates of an idea. An example of a provider of such data is MapIt UK which is an API-as-a-service developed by a previously mentioned non-profit MySociety. Given a postcode or coordinates, it can be used to determine which local authority is responsible for a given area, along with additional details such as who is the local Member of Parliament (MP) or what services are available in that area.

The additional information provided by MapIt UK could be further used to make the platform more personal by directly linking ideas to responsible MPs. Unfortunately, as the name implies, MapIt UK is only available for locations that are within UK boundaries. Data from MapIt Global, also developed by MySociety, provides only rudimentary information about larger administrative bodies, making it unsuitable for the purposes of hyper-localised platform like Urbanero. It is possible there might be similar services on offer in other countries, but an official standard for geolocating small-scale administrative boundaries does not yet seem to exist.

The lack of administrative data represents a substantial technical barrier for the development of the Urbanero platform. While a responsibility for an idea can be assigned by a citizen or claimed by a local authority, relying on manual user input is prone to error, does not scale to a large volume of differently placed ideas and opens up a possibility for misuse with potentially far-reaching consequences. Looking at this issue from a power dynamics perspective, it can be argued that governments are unlikely to prioritise and promote a data protocol that support platforms which effectively put them on the spot in literally every corner of their jurisdiction; potentially unearthing numerous instances of mismanagement and negligence in a relatively short period of time.

7.1 Limitations

The research presented in this paper lacks sufficient empirical evidence to sustain some of the bolder claims. The survey was conducted with a limited number of respondents from an unrepresentative sample from the author's social network and the prototype was only tested with a narrow demographic. However, the research compensates for the lack of primary data with extensive literature review.

From a theoretical standpoint, the paper idealises the potential of technology to solve urban problems that are profoundly socio-political and culturally-dependent, while failing to acknowledge some of the more substantial existential challenges facing cities at the outset of the 21st century. In other words, a smartphone app is not an appropriate solution to the problems that the majority of the cities are facing in the world today. While the design heuristics do present a somewhat naive viewpoint, the author would argue that those heuristics can nonetheless be used to inform the design of participatory information spaces because they embody values and principles that are worth pursuing in every aspect of human activity.

8. Conclusion

This paper has critically assessed the contemporary smart city discourse and highlighted the need to shift towards more egalitarian modes of urban governance through collective decision-making and co-creation. It has provided an extensive review of the existing digitally-mediated solutions to citizen participation, with a particular focus on the up and coming field of m-participation. The insights gained from the analysis were synthesised and used to articulate the Design Heuristics for Mobile Participation Spaces. The heuristics aim to counter the authoritarian and neoliberal notions of the smart city ideal and provide an impulse to the broader field to work towards establishing a set of universal design principles for creating inclusive information spaces for citizen empowerment and deliberation.

The utility of the heuristic framework was demonstrated by applying the heuristics to a particular set of problems with existing m-participation solutions and producing a concept for a smartphone-enabled citizen deliberation platform. The concept was validated through an interactive prototype, and research findings were communicated to a broader audience using a dedicated project homepage and a GitHub repository. The future research will look into the practical and technical aspects of developing the concept further in order to produce an initial version of the platform and start collecting empirical data.

Bibliography

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Babich, N. (2016). Microcopy: Tiny Words With A Huge UX Impact. Retrieved 29 August 2018, from https://uxplanet.org/microcopy-tiny-words-with-a-huge-ux-impact-90140acc6e42

Batty, M., Axhausen, K. W., Giannotti, F., Pozdnoukhov, A., Bazzani, A., Wachowicz, M., … Portugali, Y. (2012). Smart cities of the future. European Physical Journal: Special Topics, 214(1), 481–518. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjst/e2012-01703-3

Bauman, Z., & Lyon, D. (2016). Liquid surveillance: a conversation. Cambridge; Malden: Polity.

Brabham, D. C. (2008). Crowdsourcing as a Model for Problem Solving: An Introduction and Cases. Convergence, 14(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856507084420

Buccoliero, L., & Bellio, E. (2010). Citizens Web Empowerment in European Municipalities. Journal of E-Governance, 33(4), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.3233/GOV-2010-0232

Cardullo, P., & Kitchin, R. (2017). Being a 'citizen' in the smart city: up and down the scaffold of smart citizen participation in Dublin, Ireland. Retrieved from osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/v24jn

CitizenLab. (n.d.). Retrieved 29 August 2018, from https://www.citizenlab.co/

CONSUL. (n.d.). Retrieved 29 August 2018, from http://consulproject.org/en/

Ertiö, T. P. (2015). Participatory Apps for Urban Planning—Space for Improvement. Planning Practice and Research, 30(3), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2015.1052942

Evans-Cowley, J., & Hollander, J. (2010). The New Generation of Public Participation: Internet-based Participation Tools. Planning Practice & Research, 25(3), 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2010.503432

FixMyStreet. (2018). Retrieved 21 August 2018, from https://www.fixmystreet.com/reports

Foucault, M. (1991). Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison (Reprint). London: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1975).

Gabrys, J. (2014). Programming Environments: Environmentality and Citizen Sensing in the Smart City. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(1), 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1068/d16812

Graham, S. (2005). Software-sorted geographies. Progress in Human Geography, 29(5), 562–580. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132505ph568oa

Greenfield, A. (2006). Everyware: The Dawning Age of Ubiquitous Computing. New Riders.

Greenfield, A. (2013). Against the smart city: The city is here for you to use (Kindle version). Retrieved from https://www.amazon.co.uk/Against-smart-city-here-Book-ebook/dp/B00FHQ5DBS

Greenfield, A. (2017). Practices of the minimum viable Utopia. Architectural Design, 87(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.2127

GSMA Intelligence. (2017). GSMA Mobile Economy 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018, from https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/

Han, B.-C. (2017). Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power. (E. Butler, Trans.). London: Verso.

Harari, Y. N. (2017). Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. New York, NY: Harper.

Hindman, M. S. (2009). The myth of digital democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Retrieved from http://site.ebrary.com/id/10442060

Höffken, S., & Streich, B. (2013). Mobile Participation: Citizen Engagement in Urban Planning via Smartphones. In C. N. Silva (Ed.), Citizen E-Participation in Urban Governance: Crowdsourcing and Collaborative Creativity. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-4169-3

Kitchin, R., & Dodge, M. (2011). Code / space: software and everyday life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Klauser, F., Paasche, T., & Söderström, O. (2014). Michel foucault and the smart city: Power dynamics inherent in contemporary governing through code. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(5), 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1068/d13041p

Kleinhans, R., Van Ham, M., & Evans-Cowley, J. (2015). Using Social Media and Mobile Technologies to Foster Engagement and Self-Organization in Participatory Urban Planning and Neighbourhood Governance. Planning Practice and Research, 30(3), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2015.1051320

Korn, M. (2013). Situating Engagement: Ubiquitous Infrastructures for In-Situ Civic Engagement (Doctoral dissertation). Aarhus University, Denmark.

March, H., & Ribera-Fumaz, R. (2016). Smart contradictions: The politics of making Barcelona a Self-sufficient city. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(4), 816–830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776414554488

McQuire, S. (2008). The Media City: Media Architecture and Urban Space. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mergel, I. (2013). A framework for interpreting social media interactions in the public sector. Government Information Quarterly, 30(4), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.05.015

Mihailescu, T. (2018). Meet The Under 30 Who Is Bringing Digital Democracy To European Cities. Retrieved 29 August 2018, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/tudormihailescu/2018/08/23/meet-the-under-30-who-is-bringing-digital-democracy-to-european-cities/

Morozov, E. (2010). Technological Utopianism. Retrieved 20 December 2017, from https://bostonreview.net/archives/BR35.6/morozov.php

Morozov, E. (2014). To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: PublicAffairs.

Mozur, P. (2016). China, Not Silicon Valley, Is Cutting Edge in Mobile Tech. Retrieved 24 August 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/03/technology/china-mobile-tech-innovation-silicon-valley.html

Mozur, P. (2017). In Urban China, Cash Is Rapidly Becoming Obsolete. Retrieved 24 August 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/16/business/china-cash-smartphone-payments.html

Napoli, P. M., & Obar, J. A. (2014). The Emerging Mobile Internet Underclass: A Critique of Mobile Internet Access. The Information Society, 30(5), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2014.944726

Norris, P. (2001). Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139164887

O'Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. London: Penguin.

Paulos, E. (n.d.). Participatory Urbanism. Retrieved 21 December 2017, from http://www.urban-atmospheres.net/ParticipatoryUrbanism/index.html

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A., & Chatterjee, S. (2007). A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(3), 45–77. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222240302

Rosenfeld, L., Morville, P., & Arango, J. (2015). Information architecture: for the web and beyond. Sebastopol (CA): O'Reilly Media.

Schmidthuber, L., & Hilgers, D. (2018). Unleashing Innovation beyond Organizational Boundaries: Exploring Citizensourcing Projects. International Journal of Public Administration, 41(4), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2016.1263656

Schröder, C. (2014). A Mobile App for Citizen Participation. Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Electronic Governance and Open Society: Challenges in Eurasia - EGOSE '14, 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1145/2729104.2729137

Seltzer, E., & Mahmoudi, D. (2013). Citizen Participation, Open Innovation, and Crowdsourcing: Challenges and Opportunities for Planning. Journal of Planning Literature, 28(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412212469112

Shepard, M. (2007). Propagative Urbanism: (re)searching the living city. Retrieved 26 August 2018, from http://cast.b-ap.net/propagativeurbanisms09/

Söderström, O., Paasche, T., & Klauser, F. (2014). Smart cities as corporate storytelling. City, 18(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2014.906716

Tambouris, E., Liotas, N., & Tarabanis, K. (2007). A Framework for Assessing eParticipation Projects and Tools. In 2007 40th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS'07) (pp. 90–90). https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2007.13

Thiel, S.-K., Fröhlich, P., & Sackl, A. (2016). Experiences from a Living Lab trialling a mobile participation platform. In Proceedings of 21st International Conference on Urban Planning, Regional Development and Information Society (pp. 263–272).

Townsend, A. M. (2000). Life in the Real-Time City: Mobile Telephones and Urban Metabolism. Journal of Urban Technology, 7(2), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/713684114

Townsend, A. M. (2013). Smart cities: big data, civic hackers, and the quest for a new utopia. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Tucker, I. (2012). Surveillance and Techno-biological Living. In W. R. Webster (Ed.), Proceedings of LiSS Conference 3: Living in Surveillance Societies: 'The State of Surveillance' (pp. 107–129). Great Britain: Amazon.

Waal, M. de. (2011). The Ideas and Ideals in Urban Media. In M. Foth, L. Forlano, C. Satchell, & M. Gibbs (Eds.), From Social Butterfly to Engaged Citizen: Urban Informatics, Social Media, Ubiquitous Computing, and Mobile Technology to Support Citizen Engagement (pp. 5–20). London: The MIT Press.

Wade, S. (2017). Advanced Surveillance Spreading From Xinjiang. Retrieved 26 August 2018, from https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2017/12/advanced-surveillance-spreading-xinjiang-across-china/

Wang, M. (2017). China's dystopian push to revolutionize surveillance. Retrieved 26 August 2018, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/democracy-post/wp/2017/08/18/chinas-dystopian-push-to-revolutionize-surveillance/

Welch, E. W., Hinnant, C. C., & Moon, M. J. (2005). Linking citizen satisfaction with e-government and trust in government. Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory, 15(3), 371.

Williamson, W., & Parolin, B. (2012). Review of Web-Based Communications for Town Planning in Local Government. Journal of Urban Technology, 19(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2012.626702

Winner, L. (1997). Cyberlibertarian Myths and the Prospects for Community. SIGCAS Comput. Soc., 27(3), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1145/270858.270864

Wroblewski, L. (2011). Mobile FIrst. New York: A Book Apart.

Zuboff, S. (2015). Big other: Surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of Information Technology, 30(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2015.5