Introduction

Every day, we create 2.5 quintillion bytes of data — so much that 90% of the data in the world today has been created in the last two years alone.

We are drowning in data. We like to talk about information society, but “[m]ost of the technology we call information technology is, in fact, data technology” (Shedroff, 2000, p. 272). The 21st century is characterized by a severe information and data overload, on both an organizational and personal level (Jones, 2012; Shedroff, 2000). Industry leaders are quick to provide us with new buzzwords: Big Data, Web 3.0, Semantic Web, Deep Learning, and Internet of Things. Such terms may help familiarize the general public with the latest advances in technology, but they are often just new labels for problems that previous researchers, philosophers, and businesses attempted to address decades ago. These problems have since grown in scale. They now also affect more people than ever before. But the way we approach information and information design has not kept pace with the growing complexity of our information systems.

We may indeed be in the midst of a transition to a true information society, but in the meantime, our approach to dealing with information problems is still rooted in the mechanistic, Tayloristic view of optimum organization. Our answer to the ever-increasing flow of unstructured data and information has been overstructuring (Cooley, 2000). System designers and engineers have a tendency to base their decisions on the system's capabilities rather than human needs which the system is supposed to cater for. This leads to bloated, multi-purpose solutions that are out of proportion to what the human mind can process in a reasonable and useful manner. By framing people's problems as mere features in vast information systems, we fail to address the more fundamental issues of how people perceive and interact with the information around them on day-to-day basis. We judge the quality of the system by the number of features it has, rather than how it enhances our lives. The field of human-computer interaction (HCI) has emerged to tackle this growing disconnect between the systems and people using those systems.

HCI gained prominence in the early 1990’s and its popularity continues to rise to this day. The researchers in this field did succeed in shifting more attention to human actors, however, the concepts and ideas used are still rooted in a technocentric view of the World. Much of the research in HCI revolves around system capabilities and investigating how people manipulate data through visual interfaces, rather than how they perceive information and how it fits into the broader context of their everyday lives. It tries to extract and objectify universal truths and apply them to the design of interfaces which are usable, but not necessarily useful.

This paper examines the latest approaches to the design of human-centered information systems. These approaches are rooted in an ecological inquiry, investigating people in their natural surroundings and paying particular attention to the context of the information use. These emerging fields see people as an absolute focal point of the study. The underlying technology is of secondary interest. The utility of these post-modern perspectives on information management is illustrated on a design solution for a knowledge-sharing platform. The notion of design in this paper takes core principles from established fields of industrial design and design science. It then combines them with a more recent research from an emerging field of information design. Principles of information design are applied to conceptualize a possible solution for information problems posed by a specific context of traveling to a foreign country.

Traveling is an information-intense industry, and has been one of the most impacted industries by the massive proliferation of the Internet and social media in the last decade (Xiang, & Gretzel, 2010). Therefore, it was chosen as a suitable area of interest for this research. Moreover, this choice was motivated by the author’s own personal experience in finding and sharing relevant travel information, coupled with a long-term desire to design and develop a platform that would mediate a more authentic traveling experience. To guide the investigation, the following research question has been devised:

How to provide travelers with location-based information through harnessing collective knowledge of local residents by applying principles of information design?

The paper starts off by positioning itself in the multidisciplinary field of information management. Then it goes into examining the terminology and concepts which will be used in the analysis later on by applying the latest perspectives for the design of human-centered information systems. Following this examination, the methodology and the research design of this paper are presented, followed by the analysis with a proposal for a possible solution to the information problem at hand. The paper concludes with a summary of the key findings.

Research domain

The purpose of this paper is to improve understanding of the theoretical background for designing human-centered communication and information systems (IS). More specifically, it looks at many-to-many online knowledge-sharing platforms, with a particular focus on information-seeking behavior within those platforms. On a more practical note, it aims to provide a set of guiding principles for designing such platforms in a specific context of travel and location-based information-seeking. The proposed platform design’s function is to harness locally embedded collective knowledge of residents and travelers, and disseminate this knowledge in the form of digitized information artifacts to a wider audience online.

The research of this paper is rooted in an inherently multi-disciplinary field of Information Management (IM), drawing on concepts and ideas from various disciplines, such as communication, information systems, information science, knowledge management, information architecture, social science, and design science (Fidel, 2012; Madsen, 2012). IM operates in both an information and knowledge domain without a clear distinction between the two, as they constantly intervene throughout the paper. This ambiguity in the terminology will be further examined in the paper’s conceptual framework section.

From a traditional IM perspective, the following research spans the entirety of the Information Management Cycle, as proposed by Choo (2002), with a particular focus on the stages of information needs, acquisition, services, and distribution. The remaining stages are examined only peripherally, but nonetheless play an important role, as they are inherently encompassed in the overall design of an IS. Choo’s view on the management of the entire information value chain is more useful for examining IM from an organizational perspective, where much of the IM activity revolves around underlying technology and infrastructure. This technology-oriented IM views information primarily as a resource to be objectified, collected, stored, managed, analyzed, and distributed (Schlögl, 2005). Yet, since the overarching goal is to design a knowledge-sharing IS, certain aspects of technology-oriented IM are still going to hold relevance in the analysis, particularly within the proposed design solution.

By focusing on information-seeking behavior, this paper takes a more human-centered, content-oriented approach to IM, which is rooted in library and personal perspectives of IM (Detlor, 2010; Schlögl, 2005). While library perspective is concerned with the information needs of people (patrons), the focus is still on storing, organizing, and distributing information. This perspective takes a rather top-down approach, where the library (librarian) serves as a broadcast medium to disseminate information in a one-to-many manner with little regard for the immediate context of information use. On the other hand, the personal perspective puts an individual human actor at the forefront. Here, IM is less about technical solutions and more about the human-side of IM. After all, it is humans who “add the context, meaning and value to information, and it is humans who benefit and use this information” (Detlor, 2010, p. 107). The field of study of personal information management (PIM) stems from this human-oriented perspective.

Much of the early study of PIM is grounded in the traditional techno-centric branch of IM. In this view, the actor’s interaction with information is seen through a simplistic perspective, where the interaction is often depicted by static input, output models (Jones & Teevan, 2007). The focus is on the manipulation of information items and interfaces that mediate the interaction, rather than on the interaction itself and the context it occurs in. The study of PIM is an integral part of the human-computer interaction (HCI) field, but the growing realization that “our interactions with information are much more central to our lives than are out interaction with computers” (Jones & Teevan, 2007, p. 18) has lead to an emergence of a new branch of study called human-information interaction (HII).

This paper positions itself in this up-and-coming field of HII, which establishes the human actor as the study's prime focal point. Therefore, this study takes a naturalistic approach to PIM, by stressing the importance of various contexts and information spaces in which people interact with information and make sense of the world around them (Fidel, Pejtersen, Cleal, & Bruce, 2004; Naumer & Fisher, 2007). It is a holistic perspective that acknowledges the need to study people's interaction with information in the natural setting it occurs in. This ecological inquiry needs to be conducted in a cross-disciplinary manner considering “cognitive, physical, neurological, social, emotional, and economic aspects of interaction, among others” (Fidel, 2012, p. 1).

It is not technically feasible to study people across every single context they immerse themselves in on a daily basis. Yet it is still reasonable to conduct research within a specific context. Although with such a study, it is necessary to acknowledge the complex cross-contextual nature of human life and that “personal information and methods for managing it may move between these contextual boundaries” (Naumer & Fisher, 2007, p. 76).

By applying the latest approaches to HII, this paper examines problem-based information needs within a specific information space in a context of travel. This information space is set in a broader activity space where physical action and physical experiences occur. “In order to undertake activities in the activity space, people need access to information” (Benyon, 2001, p. 427). Therefore, principles of information design are applied to conceptualize a possible IS solution that would provide access to locally relevant information artifacts in a temporary information space of travel, while staying compatible with the flux of contexts of everyday human activity.

Due to the inherently broad, multi-disciplinary, and ambiguous nature of the conceptual framework, the findings are generalizable to a greater or lesser degree. With minor adjustments, the research design, methods, concepts, and models used throughout this paper can be repurposed for analyzing and designing online knowledge-sharing platforms that focus on contexts other than travel.

Conceptual framework

This section of the paper aims to improve understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of HII and information design—two young, emerging fields that have roots in more traditional fields of library and information science (LIS), PIM, HCI, IS design, and design science. Moreover, it serves as a theoretical framework for the analysis presented later in this paper. First, the basic concepts and terminology are examined, as to clarify their meaning for this paper’s purposes. The next sub-section aims to shed light on the evolving role of design in society. It examines the historical position of design as an all-encompassing human endeavor and its gradual transformation into a formalized field. This section concludes with conceptual models which will be applied in the analysis.

According to Schrader, who studied 700 definitions of “information science” from 1900 to 1981, “the literature of information science is characterized by conceptual chaos” (as cited in Myburgh, 2005, p. 13). Rapid technological advances, widespread adoption of portable computing devices, and growing ubiquitous access to the Internet have characterized the turn of the 21st century (eMarketer, 2014a, 2014b; Internet Live Stats, n.d.). This has lead to a growing realization of the central role information plays in our everyday lives, and to a further conceptual and semantic confusion surrounding IM's core terms like data, information, and knowledge (Myburgh, 2005).

To accommodate for the ambiguity in terminology and interpretation of concepts, this paper takes a strong interpretivist view rooted in social construction, looking “for culturally derived and historically situated interpretations of the social life-world” (Crotty, 1998, p. 67). It strives to avoid a pitfall of false dichotomies that separate analytical concepts into neatly confined boxes with limited applicability to real world problems, if taken at face value. In this view, virtually any claim is valid to a greater or lesser degree. While this allows for a substantial freedom in the analysis, it also renders the outcomes of the analysis inconclusive. In other words, this paper claims to provide a “good enough” solution to a research problem at hand, but it does not (and by the definition it cannot) conclude with an all-encompassing answer with a single “correct” solution. The entire paper is based on this modus operandi.

The paper’s pragmatic nature stems from a phenomenological tradition in which the object and the subject are inherently interlinked—one cannot be adequately described without the other (Crotty, 1998). Rather than trying to objectify and isolate some sort of “reality out there,” the focus is on human experience of the world, not the world itself (Fidel, 2012). It studies differences in the interpretations of the world, what aspects of our everyday life and environment affect these interpretations and how. In this view, the object of study is not information itself, but rather the role information plays in a wider context of work, study, and life in general (Bawden & Robinson, 2012; Wilson, 2006). The paper looks specifically for the role information plays in the context of travel.

HCI has traditionally been concerned with the study of PIM and information needs in IS design. In the world where people are drowning in data, HCI “has not really kept pace with the changes in technology” (Benyon, 2001, p. 426). This system-centric view sees the user as outside the computer and focuses primarily on how people manipulate data through interfaces. It investigates how people consume information, rather than how they comprehend it and integrate it in the broader context(s) of their everyday lives. What we call information systems, are in fact, often just data-manipulation systems. The design of these systems is usually driven by the capabilities of the given technology, rather than by the information needs of the end-user (Albers, 2008; Benyon, 2001; Wilson, 2000).

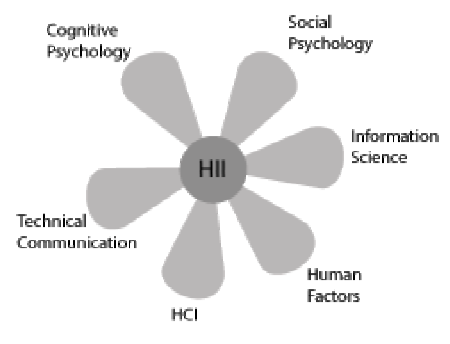

The growing realization of the inadequacy of HCI to cope with increasingly information-dense nature of everyday life has lead to an emergence of a new field of HII. This field has marked a “a philosophical shift of privileging the human’s interaction with the information, rather than the human’s interaction with the computer interface” (Albers, 2008, p. 117). This naturalistic view sees technology merely as an enabler, not the point of interest. It moves the human actor from outside to inside an information space in which “people must perceive and interpret the information artefacts so that they can achieve their goals in an activity space.” (Benyon, 2001, p. 429). The focus is on “on people interacting with information and solving problems” in an activity space, where their everyday experiences occur (Albers, 2008, p. 118). HII strives to uncover how people conceive information, rather than how they merely perceive it (Benyon, 2001). At the end of the day, a “person does not want to use a web-based information system or a computer application; they want to accomplish a real-world goal” (Albers, 2008, p. 118). The term human information behavior (HIB) is sometimes used to describe essentially the same concept as HII. In this paper, the term HII is preferred, but both can be used interchangeably (Jones, 2012; Jones & Teevan, 2007). The Figure 1 illustrates the multidisciplinary nature of the field.

Figure 1 - Fields involved in successful communication of technical information. Adapted from Albers (2008)

3.1 Terminology

As mentioned earlier, there is quite a bit of conceptual confusion and a lack of consensus surrounding many of the terms central to the study of IM, and the various disciplines it encompasses. The word “information” is understood differently if one is an engineer developing a new enterprise intranet, than if one is a communications expert analyzing a political debate on television. One sees it as a resource existing independent of the human mind, while the other sees it purely as product of human interaction. The following is a rough delineation of some of the key terms used throughout the paper and how they are understood for the purposes of this research.

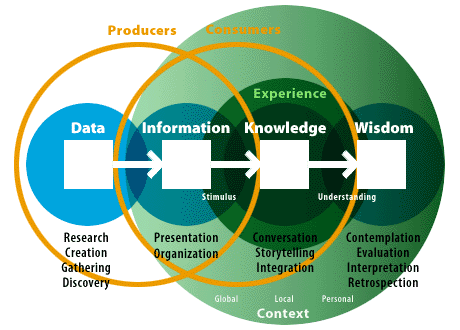

Data

Data is a raw representation of something factual and quantifiable. It is created through measurement and direct observation. Moreover, it can be received, stored, processed, and transmitted by humans, computers, and other mediums (Myburgh, 2005). Data do not have an intrinsic discrete meaning and are therefore not an adequate product for communication (Myburgh, 2005; Shedroff, 2000). To obtain value from data, it must be transformed, organized, and given meaning. Once a human actor has made sense of data, it becomes information. Data can be subsumed under information in a sense that “data may or may not be information depending upon the state of understanding of the information user” (Wilson, 2000, p. 50).

Information

Information is a product of human interaction with data and that “part of an individual's knowledge which can be communicated, which has meaning and which can be understood by other individual” (Myburgh, 2005, p. 24). Information has meaning, as opposed to data. The term is often conflated with the terms data and knowledge, as it is typically used to describe different things in different contexts. In the early study of IM, information was often viewed as something that could exist independently of the human mind and the medium that is used to carry it. In this system-centric view, the information is objectified and seen mainly as a resource to be managed and manipulated. Today, more established notion sees information exclusively as a product of a communicative interaction process set in a certain context (Bawden, & Robinson, 2012). When we talk about information as an independent entity residing outside of the human mind, we are talking about an information item or an information artifact. That is the “packaging of information in a persistent form than can be acquired, created, viewed, stored, grouped (with other items), moved, given a name and other properties, copied, distributed, moved, deleted, and otherwise manipulated” (Jones & Teevan, 2007, p. 7). Another term used for an information item is a document, which refers to any recording of information (Myburgh, 2005).

Knowledge

Knowledge can be broadly described as “that which people know and is accumulated through understanding, interpreting, analysing and making meaning of what is experienced and observed, as well what others have communicated” (Myburgh, 2005, p. 22). It is derived from both data and information, dependent on personality and intellect. Therefore, everyone possesses a highly personal unique body of knowledge that resides inside his or her head. Every knowledge management system is inherently trying to separate knowledge from the mind to a greater or lesser degree. Management studies in particular have grown fond of the notion of the tacit knowledge, popularized by Nonaka (1991). This view argues that an organization can tap into hidden knowledge in the heads of the organizational members by devising appropriate methods and processes to translate tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge that can be communicated to the rest of the organization. This again suggests a rather system-centric view, where knowledge is treated as a commodity to be captured, codified, and seen primarily as an organizational asset. In the tradition of Polanyi (Tsoukas, 2003), this paper treats knowledge as something highly situated and entirely ineffable. It cannot be transmitted, only information about the knowledge can, and “that information can only ever be an incomplete surrogate for the knowledge” (Wilson, 2000, p. 50). When a person interacts with information and uses it to solve a problem or achieve a specific goal, knowledge can also be seen as information in action (Hughes, 2002). The concept of wisdom is beyond the scope of this paper, and is regarded as a highest form of knowledge that has accumulated over a long period, and is impossible to communicate.

Figure 2 - The Understanding Spectrum. Illustration of the relationships between the key terms. Adapted from Shedroff (2000)

Information behavior

Wilson described information behavior as “the totality of human behavior in relation to sources and channels of information, including both active and passive information seeking, and information use” (Wilson, 2000, p. 49). This broad term includes face-to-face communication, as well as a more passive reception of information with no intention to “act on the information given” (Wilson, 2000, p. 49). For a long time, research into information behavior has been dominated by an inquiry into the cognitive dimension of human life. Human-information interaction is a cognitive process after all—not a social or physical one. However, this perspective severely underplays, or completely ignores, the role of other dimensions like social or environmental (Fidel et al., 2004). It is therefore necessary to adopt a more multidimensional, ecological approach that also includes the social dimension which “views the human as a person who lives and acts in a certain context, rather than a user of information systems and services” (Fidel, 2012; Fidel et al., 2004). The ecological approach to HII starts with the study of environmental constraints before moving onto the investigation of cognitive constraints. In this view, “interacting with information is a way to overcome an obstacle in solving a problem” (Fidel, 2012, p. 7). The importance of the information itself is downplayed in favor of examining the problem-based and pragmatic nature of the interaction since “most of the time, people are trying to solve problems, to make sense of the world, and to do things, not find information for its own sake” (Bawden, & Robinson, 2012, p. 205).

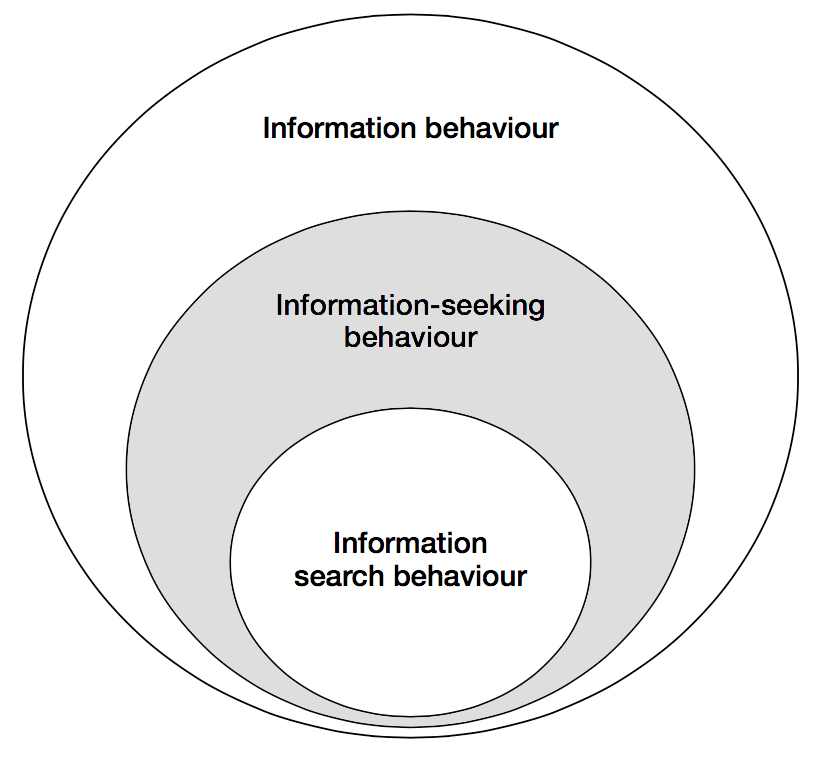

Human processing of information is not seen as a static input-output process, but rather as a continuous act of sense-making which “focuses on how people understand information they receive within their life context, with factors such as the person’s expertise, social position, and situation affecting their understanding” (Fidel, 2012, p. 59). As information behavior as a research area is too broad, this paper has chosen a subset of information-seeking behaviour, which is concerned with the information needs, as a primary area of research, as illustrated in Figure 3. Information search behavior is “the ‘micro-level’ of behavior employed by the searcher in interacting with information systems of all kinds” (Wilson, 2000, p. 49). It focuses on the interaction with the system on both the interface, and the intellectual level and is implicitly contained within the term information-seeking behaviour.

Figure 3 - A nested model of the information seeking and information searching research areas. Shading added by the author to highlight the area of interest. Adapted and modified from Wilson (1999)

Information needs

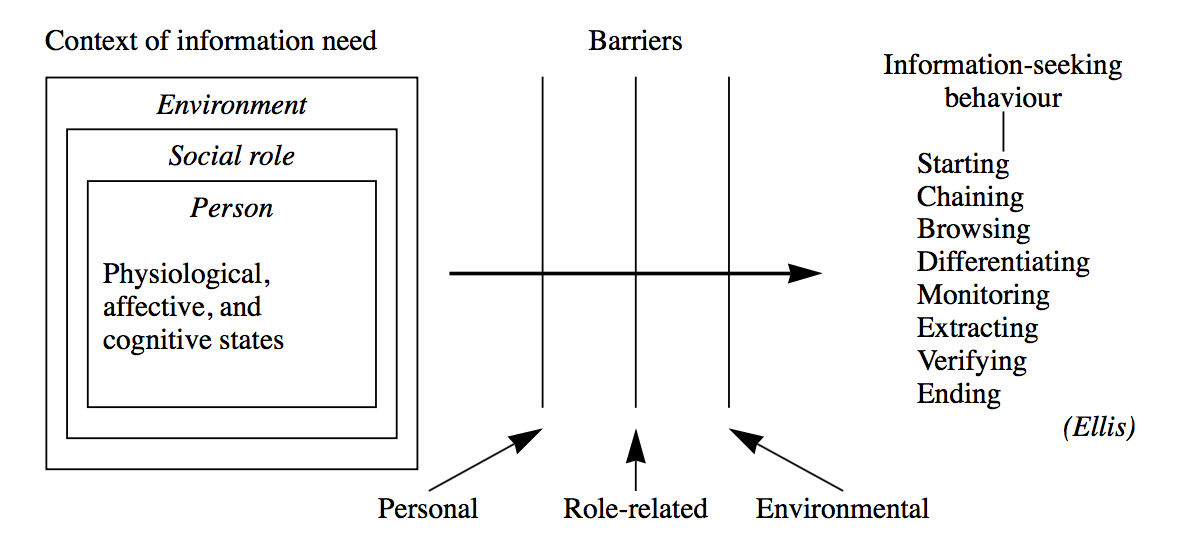

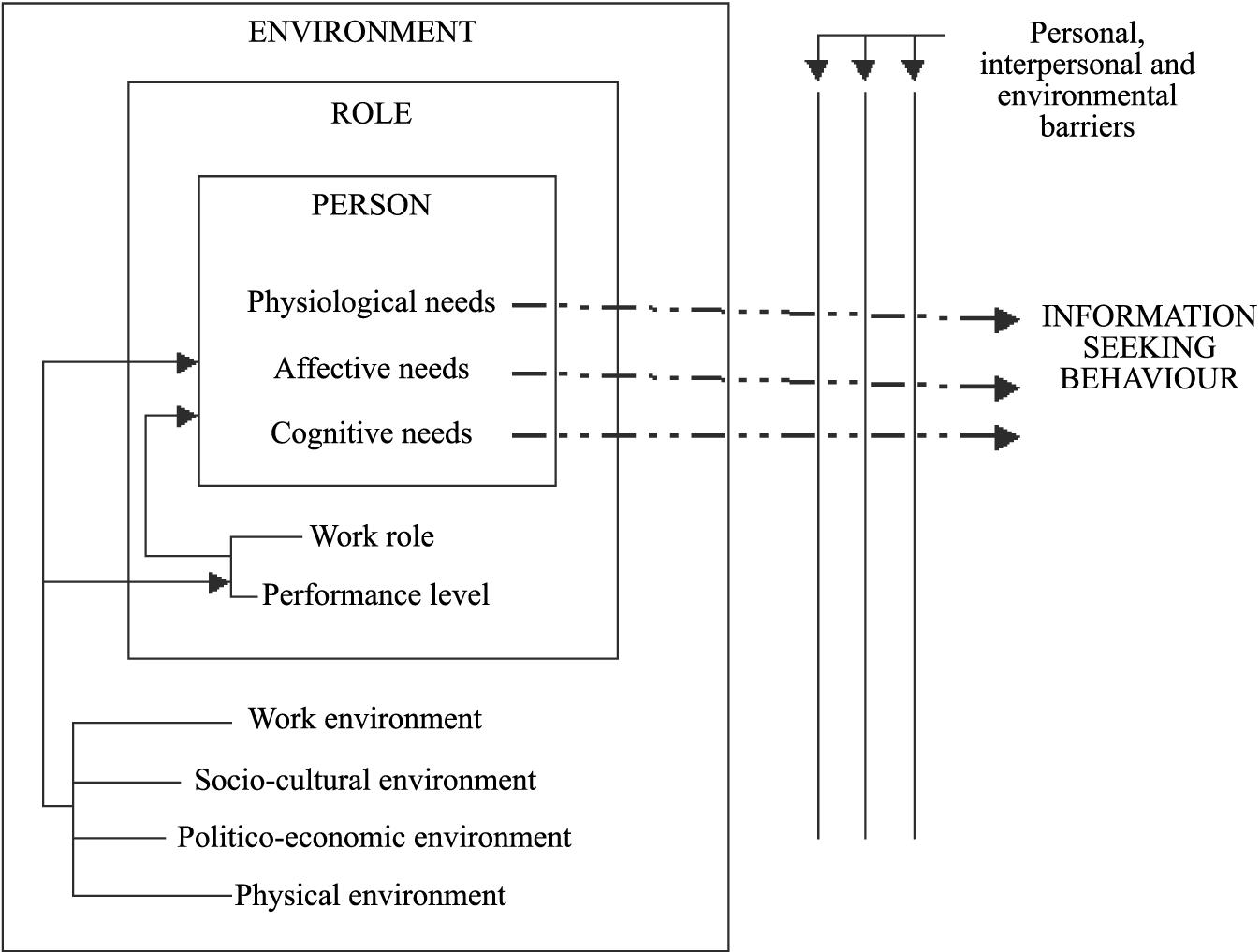

Information need is a secondary human need that arises out of more basic, primal needs (Wilson, 1999). In the problem-based view, information is seen as a tool that people use to cross a barrier they encounter when they try to achieve something, such as obtaining food, finding shelter, satisfying their curiosity. Here the information need is defined by uncertainty and an “actor’s realization that she misses something that is required to move from one situation to another” (Fidel, 2012, p. 176). Wilson (2006) suggests that the term information need implies a concrete entity residing in an actor’s mind, and the goal of a researcher is to simply figure out what these needs are. Assumingly, this simplistic conceptualization of information needs is the reason behind a relatively low effectiveness of traditional consumer research in terms of figuring out the actual desires of people (Gócza, n.d.). Wilson goes on to suggest that instead we speak of “information seeking towards the satisfaction of needs” which sees the “full range of human, personal needs […] at the root of motivation towards information-seeking behavior” (Wilson, 2006, p. 665). This perspective suggests a more complex interplay of human mind, context, social setting, and environmental constraints (see Figure 4). Information needs are then seen as being an abstract concept in a constant state of flux, always changing depending on the current context, broader socio-psychological state, and the current role of the information user.

Figure 4 - Wilson’s model of information-seeking behaviour. Adapted from Wilson (1999)

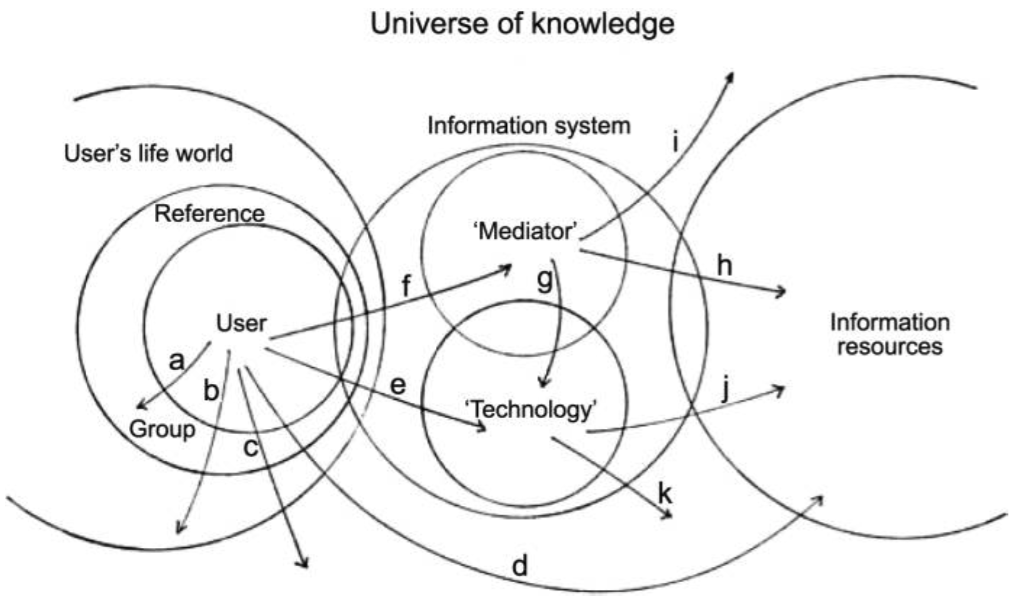

Much of the study of information-seeking behavior revolves around a single role in a person’s life. Most notably, organizational and management studies often only consider the work role of the people, ignoring their active roles as parents, students, politically engaged citizens, and countless other roles people take on over the course of a single day (Wilson, 2006). As mentioned in the previous section, investigation in a single context is not inherently an exercise in futility, but it is necessary to acknowledge that people might occupy several roles simultaneously and that there is always an array of contexts influencing a task-at-hand. Figure 5 serves as a good illustration of the complexity involved in a seemingly simple act of looking for information using only a single information system.

Figure 5 - The context of information seeking. Illustrates a variety of overlapping contexts when using a single information system, arrows show some of the possible search paths. Adapted from Wilson (2006)

Actor

There are various terms used to describe a person interacting with an IS. Librarians call such people patrons. In the corporate context they are sometimes referred to as clients. Undoubtedly, the most widely used term is users. “All these terms include only those who actually use a system and ignore potential users who may also benefit from using it” (Fidel, 2012, p. 4). On the other hand, the term actor implies a sense of agency and shifts the focus from the system to the participant, who has an existence outside of the information system. It highlights the importance of HII taking place in a context(s) of activities. Furthermore, this conceptualization forces us to also consider the nonusers, who may be reluctant to use an IS because their information needs have not been satisfied (Fidel, 2012). The term user is occasionally used throughout the paper to avoid clumsy wording, but generally actor is the preferred term.

3.2 Design meets information

Overload, clutter, and confusion are not attributes of information, they are failures of design.

With the rapid adoption of the World Wide Web in the last two decades, the term “designer” became strongly associated with a small subset of visual design. Today, when we say designer, most people think of a person that builds websites, creates screen-based interfaces, and is concerned primarily with the digital, or print medium. Design as a craft is much older than the Internet culture would lead us to believe. If taken in its broadest sense, design has always been present, and is in one of the most fundamental human activities. In the words of one of the founding fathers of modern human-centered design:

All men are designers. All that we do, almost all the time, is design, for design is basic to all human activity. The planning and patterning of any act toward a desired, foreseeable end constitutes the design process. Any attempt to separate design, to make it a thing-by-itself, works counter to the fact that design is the primary underlying matrix of life.

Historically, there were three types of designers. The do-it-all master generalists, the likes of Leonardo Da Vinci, who have engaged in every conceivable act of creative endeavor. They created innovative solutions to day-to-day problems, and designing new tools, methods, and entire cities for their patrons. Then a more specialized craftsmen, who have mastered the art of design through know-how passed on for generations of family-run businesses. And later through tapping into the collective knowledge of guilds. And lastly, there were everyday “laydesigners”.

Prior to advances in mass production, the majority of communities and families have directly participated in the process of designing/building their dwellings and everyday objects around them. “The connection between designer/builder and end-user was direct” (Papanek, 1995, p. 103). Vernacular architecture and design use locally sourced materials and methods to build structures that are designed directly around the needs of people using them. Such structures are more sensitive to a particular context of use and local environment, and are build on human scale. This idea is based on respecting natural proportions, stemming from the principles of organic and biomorphic design and translating them into man-made system or objects (Papanek, 1983). It is directly opposed to gigantism, and admiration of bigness brought upon by industrial revolution. The concept of human scale was coined by Kohr (1957) in The Breakdown of Nations where he applied it to the size of political groupings. This concept was later popularized by Schumacher (1973) who placed an economic twist to it in his Small is Beautiful. Papanek (1983) outlined a strategy for a sustainable, and honest design in his Design for Human Scale.

Formalization of design combined with the evermore efficient means of mass production have certainly accelerated technological and cultural progress. At the same time, they have made design inaccessible to the majority of people. Making it a matter of the so-called experts, concentrated in academia and business, not something concerning everyone. Perception and knowledge of design sensible to people’s lives is something that benefits everyone. Despite that, appreciation for good design is mostly self-taught, or acquired through higher education. This also creates a negative effect in a form of ethnocentrism from a perspective of designers. Artistic expression and newness-for-the-sake-of-newness take primer over utility of the objects they are designing. Design becomes less inclusive, a “game played by an increasingly small elite, with a complete disregard for people” (Papanek, 1983, p. 6). Designing primarily for the constructed needs of a small fraction of population in abundant societies, often neglecting people with special needs, and those with limited access to conveniences of the modern life. Putting aside a moral issue with such approach, it also deprives us of truly inclusive designs, because “if we […] lump together all the seemingly little minorities […], if we combine all these ‘special’ needs, we find that we have designed for the majority after all” (Papanek, 1972 ,p. 68).

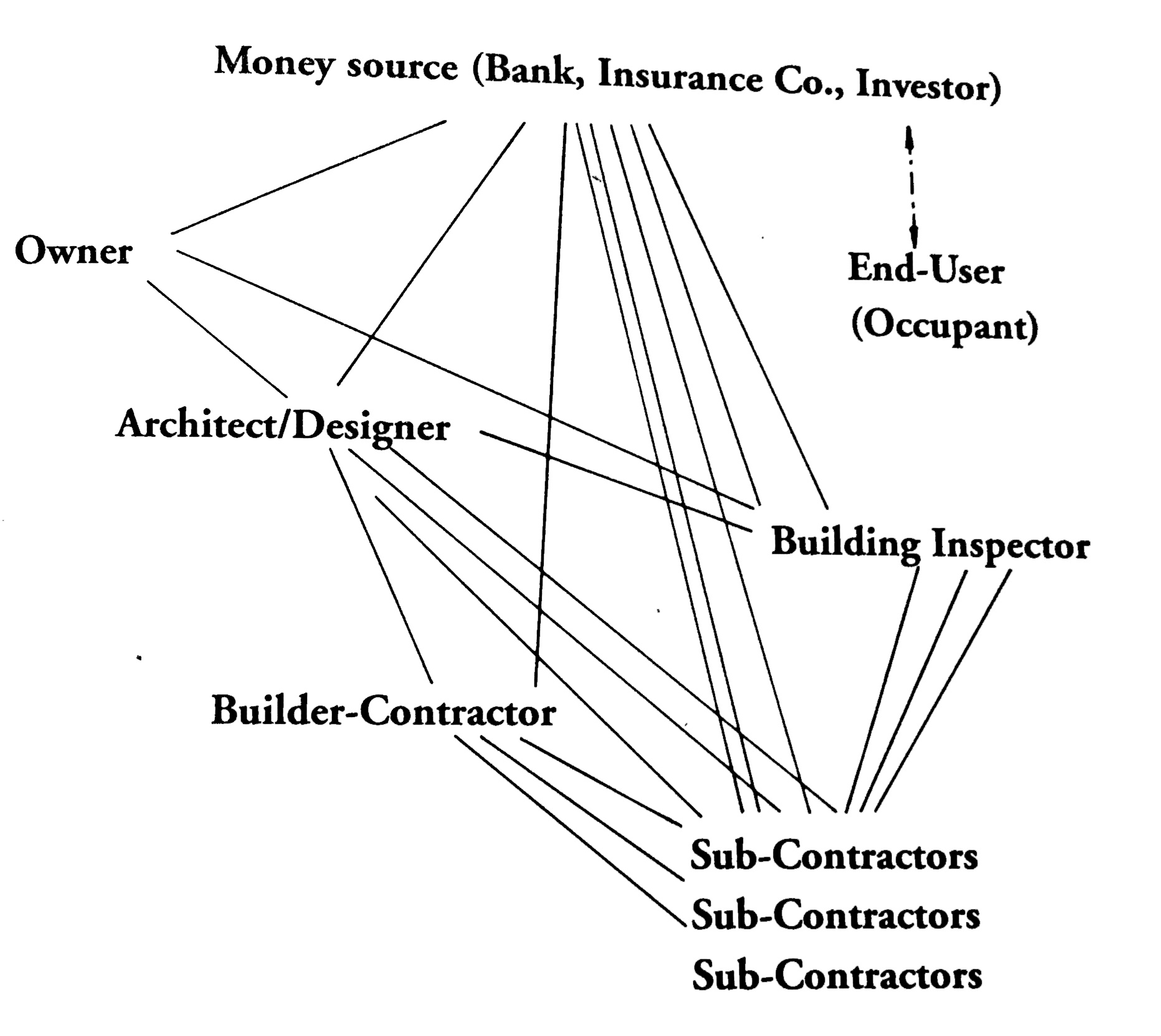

Papanek (1995) illustrates this disconnect between designers and people experiencing their designs on a constellation of people involved in building a house in which an architect/designer never comes in contact with the house occupant (for a diagram see Appendix 1). This can easily be translated to a modern example with design and development activities scattered around various organizational silos. Direct contact with customers mostly occurs through customer support and marketing research departments. Solutions are designed for people, not with people.

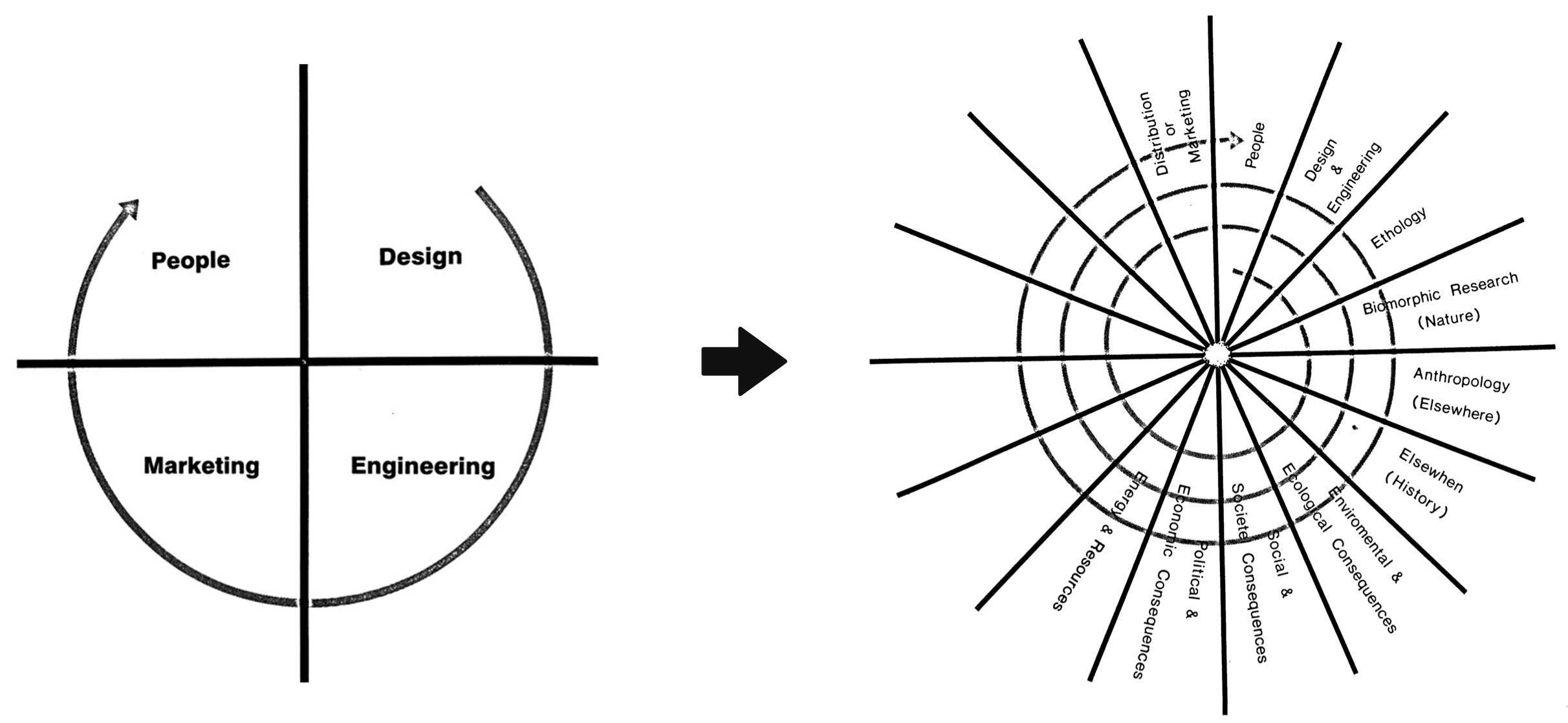

A traditional design based on a waterfall model(s) begins with designers, then it is engineered, then marketed and given to the people in the end (see the first diagram in Figure 6). Subsequently, the end-user feedback is incorporated only peripherally and after the design has already been completed. This approach neglects the fact that the design process should both begin, and end with people. Papanek (1983) suggests a more iterative design process flowchart (see the second diagram in Figure 6). In his conceptualization the flow starts with people, and is represented with a spiral, rather than a single arc, implying a more dynamic and continuous process with reoccurring feedback loops. Moreover, it acknowledges the changing nature of design by leaving empty spokes for including new design methods that may arise in the future.

Figure 6 - From static to dynamic design process flowchart. Adapted from Papanek (1983)

Rise of a designer

By the 20th century, design started to emerge as a stand-alone field. In 1920s Bauhaus established itself as a leading school of thought in design, and continues to have an influence on the field to this day. Bauhaus brought fort a more critical inquiry into the relationship between people and their man-made environment. This school of art was at times criticized for prioritizing form over function, and was considered élitist and alienating by some. Nevertheless, it inspired many great designers, and paved the way for a design as a profession in and of itself.

Yet it was the two World Wars that accelerated technological progress. Countries and organizations pressed for resources have realized the importance of good design, and the benefits of building systems that provide a better human fit. In order to achieve this, the field of industrial designer has emerged. The field gained popularity in part thanks to a celebrity industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss. His work on cars, airplanes, ships, telephones, typewriters, vacuum cleaners, and countless other everyday objects, still surrounds us to this day. Dreyfuss’s Designing for People (1955) is considered a classic among industrial designers, and has motivated entire industries to reconsider their approach to design. First and foremost Dreyfuss was a practitioner, primarily concerned with pragmatic aspects of design. Other famous design thinkers include Victor Papanek, R. Buckminster Fuller, and Donald Norman, whose work combines social commentary with foundations of human-centered design.

Industrial design returned the human element into a world blinded by capabilities of the latest technology. It helped transform crude machinery into more enjoyable systems, that have a higher tolerance for human error, and are more sensitive to the context of use. The primary goal of industrial design is to aid the design of physical affordances of the systems we use. This is achieved through the study of human factors and ergonomics. It attempts to answer a question of how to make things more comfortable to use. As industrial design operates in a relatively well structured environment, the utility and purpose of the objects being designed is often defined in advance. For example, a car is used to get one from a point A to a point B, and thus designers do not have to ponder about the purpose of the car. They just need to make the driving experience as pleasant and hassle-free as possible. Information technology has fundamentally changed this relationship between designers and the purpose of the objects they are designing.

Hitherto, many designers would enter the field from an engineering background. An engineering mindset is well suited for structured, well-defined problems, but not as much in the ever-changing, ephemeral digital world. The wide adoption of personal computers and information technology shifted the focus from physical to cognitive aspects of design. The challenge of design shifted from how to sit a person comfortably in front of a machine to a matter of figuring out how to make the machine aid human mental processes. This shift required designers to move away from the compartmentalized physical world, and move into the uncertain realm of human mind, where semantics and pragmatics of information use are not known beforehand (Choo, 2002). Here, the role of a designer is not to simply create an object, but to give it purpose as well. To be able to do so effectively, designers need to build a sense of empathy for the end-user, and familiarize themselves more closely with the context(s) where their designs are being used. Design becomes a much more experimental process in which designers try to uncover the hidden side of human behavior.

In 1990s when the time Internet started to emerge and gain traction with the general public, a field of HCI emerged. The field was a direct answer to an increasingly ubiquitous access to personal computers. Increasingly complex information systems required increasingly complex user interfaces. This new field has introduced a more robust methodology for conducting ethnographic research in relation to design of information systems. It was, however, still rooted in the engineering tradition. As a consequence, solutions were often based on the capabilities of any given system: packing software with every conceivable feature, and stashing away the complexity behind dropdown menus (Cooley, 2000). It followed the mindset of “build it and they will come”, in which the majority of feedback was collected after the design was already completed. This era of design has produced systems that were usable but bloated and vastly over proportionate to the everyday task that they were intended to aid. Assumingly, this was in part a consequence of designers focusing on the organizational information systems and office software. Such designs try to incorporate all of the existing organizational processes into the systems, instead of rethinking those processes from the ground up.

It took another decade and the Dot-com bubble for designers to radically rethink the way they design information systems. More specifically, the launch of the first Apple iPhone in 2007 marked the beginning of a new era in design. While resistive touchscreen technology existed in the past, it was iPhone's capacitive touchscreen that brought this type of interaction with digital interfaces to a mainstream use. It represented a radical shift in the way we interact with the content on the screens around us. It removed the need for navigating with mouse and keyboard, which require a certain level of mental abstraction in order to grasp spatial relations and causality on the screen. Modern touch screens let people interact directly with the content, representing an entirely “different tactile relationship to information” (Andreessen, 2015). This offered designers new possibilities for more immersive experiences, but it also posed a serious constrain, primarily due to much smaller screens and also shorter attention span of the Internet users (Weatherhead, 2014). Suddenly designers were not able to simply hide functionality in endless menus. As a result, services and tools became much more focused, and appear to be more problem-oriented. Mobile first design became a new way to conceptualize digital interfaces. This design mindset, proposed by Wroblewski (2011), suggests that every design should start with a bare minimum of the most important content (mobile screen), and gradually layer complexity for larger screens (desktop).

The new category of touch devices renewed interest of designers in information architecture, which has traditionally been a part of LIS. It has also created a whole new job market for user experience (UX), and user interface (UI) designers. These professions existed in the past, but they were considered exotic in a way and only the largest organizations could afford to have such specialized personnel. Now, such designers are a necessity for a successful venture. UX design in particular has significantly improved people participation in the design process, and made ethnographic research a priority for many companies. Unfortunately, it often gets conflated with the UI design (Krishna, 2015), putting the focus again on the interface, and the underlying technology, rather than the person using the system. Also, there is now more tooling available to designers than ever before. According to Papanek (1972) designers can become victims of tyranny of absolute choice because “[w]hen everything becomes possible, when all the limitations are gone, design and art can easily become a never-ending search for novelty, until newness-for-the-sake-of-newness becomes the only measure” (p. 42). This pursuit for newness has been most apparent on the Web, with many designers blindly following the current trends, without ever revisiting the core underlying purpose of their designs.

The field is slowly waking up to a new reality of a never-ending flow of data with no prospect of taming it. There are industry calls for more seamless, less algorithmic designs, and building things that “do not scale” (Krishna, 2015; Graham, 2013). Solutions that do not involve screens for the sake of screens, but choose the medium most appropriate for a given context. The more advanced designs can even predict context(s) and adjust their functionality accordingly. Organizations are also trying to switch their focus from technologically-oriented solutions, to a more problem-based ones, by using Agile and Lean methodologies (Klein, 2013).

These new and evolving approaches to design signal an industry-wide paradigm shift. A design independent of the technology, applied “to the media through which information flows” (Jacobson, 2000, p. 2). Here, designers focus on “the continual development of rich interaction techniques and tools to support user’s ability to create and shape external representations of knowledge that ultimately support more effective situation awareness and understanding” (Pirolli, & Russell, 2011, p. 2). The author of this paper, subsumes these new approaches to design in the term information design; a young, ill-defined field with little consistency and consensus across academia.

Information design represents a “philosophical shift of privileging the human's interaction with the information, rather the human's interaction with the computer interface” (Albers, 2008, p. 117). It challenges menu-driven interactions (Cooley, 2000), and calls for a more context-specific information systems (Fidel, 2012). The focus is on edification, the process of personal enlightenment. It is a bottom-up approach in which “information designers seek to edify more than persuade, to exchange ideas rather than foist them on us” (Jacobson, 2000, p. 1). The proposed solution presented later in the paper strives to adhere to these principles of information design.

3.3 Relevant models

Models in HII research can be divided into three main categories: descriptive, process, and complex. Descriptive models take a form of a simple diagram or a list, as their function is to merely list “the factors and activities involved in the aspects of information behaviour being considered” (Bawden, & Robinson, 2012, p. 193). Process models introduce a certain causality to the study of information behavior by showing an order of phenomena occurring. They are often represented as flow-charts or process diagrams and are the most commonly used category (Bawden, & Robinson, 2012). The most advanced models “introduce a greater degree of context and an increased number of perspectives, and are typically non-linear or multidirectional, rather than having a single sequence of steps” (Bawden, & Robinson, 2012, p. 197). These complex models capture more of the complexity of information behavior, but they are also much harder to apply in a reasonable manner. Due to the scope of the project and lack of sufficient longitudinal data, this paper utilizes the simpler process models while acknowledging the lower explanatory power of applying these models.

The problem-based nature of the information-seeking behavior fits well with the notion of sense-making—a term commonly encountered in the literature on HCI and HII. It is “framed as the process of forming and working with meaningful representations in order to facilitate insight and subsequent intelligent action” (Pirolli, & Russell, 2011, p. 1). It cannot be seen simply as a model of information-seeking behavior, but it is, rather, a set of assumptions, theoretical perspectives, and methodological approaches which serve as an overall framework for the study of how people interpret, and make sense of the world around them (Wilson, 1999).

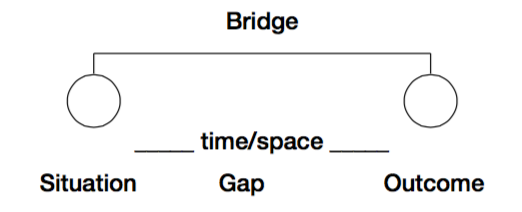

The first model in the analysis utilizes the Dervin’s Sense-Making framework as conceptualized by Wilson (1999), and is illustrated in Figure 7. A situation is set in time and space, and defines the context in which information problem arises. A gap is defined by uncertainty and represents the difference between the contextual situation and the desired situation. An outcome is the consequence of the Sense-Making process. A bridge is a means of closing the gap between situation and outcome (Wilson, 1999).

Figure 7 - Dervin’s Sense-Making framework modified. Adapted from Wilson (1999)

The second model used in the analysis is the “information needs and seeking” conceptualization as proposed by Wilson (2006), and illustrated in Figure 8. This model will be used infer information needs from more primal, human needs and to investigate the environmental, socio-psychological, and role-based constraints.

Figure 8 - Information needs and seeking. Adapted from Wilson (2006)

Methodology

This paper takes a naturalistic, discovery-oriented approach to inquiry that puts “no prior constraints on what the outcomes of the research will be” (Naumer, & Fisher 2007, p. 77). Naturalistic inquiry is holistic and contextual, decoupling research from specific technology, or setting (Naumer, & Fisher 2007). That is not to say, that a specific technology will not be proposed for the design of the IS, or that an actor will not be examined in a specific context. Instead it means that analysis, leading to the specific applications, is informed by a broad range of factors which are not concerned with particularities of travel, or a concrete choice of technology, e.g. a person's social status.

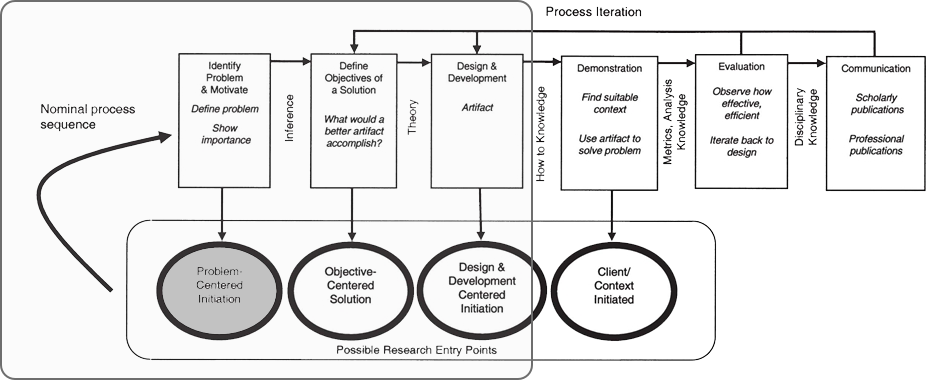

The pragmatic nature of research presented in this paper does not lend itself to traditional research methodologies. Therefore, a Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) as proposed by Peffers, Rothenberger, Tuunanen, & Chatterjee (2007) is applied. By applying DSRM, this paper does not try to understand reality, but in a tradition of design science it “attempts to create things that serve human purposes” (Peffers et al., 2007, p. 48). The core principle of this methodology is that it must produce an artefact created to address an observed problem. Production of the artefact is only a third step in the DSRM process. The subsequent demonstration, evaluation, and communication are an integral part of an iterative process to develop and design a satisfactory IS. Given the limited scope of this paper, the last three stages are omitted, and the focus is solely on the first three stages. These stages are (in the order they occur in):

- Problem identification and motivation: Defining the research problem and justifying the value of designing a solution to that problem.

- Define the objectives for a solution: Infer objectives of the IS on which the appropriateness of the designed artifact will be judged. This stage requires knowledge of the state of the problem, and current solutions and their efficacy.

- Design and development: Creating an artefact which can take various forms. Conceptually, it can be any designed object in which a research contribution is embedded in the design.

The stages relevant for the purposes of this paper are highlighted in Figure 9, together with a problem-centered point of entry.

Figure 10 - DSRM Process Model. Model with a highlighted area of interest and point of entry. Adapted and modified from Peffers et al. (2007)

4.1 Data collection

The primary data is based on exploratory interviews and an online questionnaire. This primary data is supplemented with secondary data from existing research into human-centered approaches to IS design. The naturalistic and pragmatic approach to the inquiry naturally lends itself to qualitative data. Quantitative data is seen as way to objectify a complex reality and is deemed unsuitable for the purposes of this research.

The first set of empirical data was collected through an unstructured, exploratory interviews with students at the premises of Copenhagen Business School in Copenhagen, Denmark. A total of six people were interviewed, three individually, and three as a part of a group conversation. There were no assumptions or hypothesis prior to these interviews. The interviews were conducted in a conversational manner with no set questions. The purpose was to gain an overall idea of how people perceive their habits when it comes to finding information when traveling. Certain commonalities were identified, which served as a foundation for creating an online questionnaire. As the goal was to obtain qualitative data, the questionnaire included a very small number of open-ended questions. The questionnaire utilized a “logical jumps” feature, which determined the type of questions being asked based on the answer from the first question. By dividing the questionnaire into several logical branches, it was possible to have questions that asked the respondents to compare and contrast the different methods they use to look for travel-related information (the shortest path comprised of two questions, the longest of six). The design of the questionnaire relied heavily on people’s willingness to type out their answers, and thus there were instances where the respondents skipped all the open-ended questions and answered only the first one, used to determine which logical branch to present. Yet the majority of respondents filled out all the questions, some with simple keywords, while others with concise paragraphs of text. There were a total of 31 respondents, who spent an average of 6 minutes and 1 second spent on completing the questionnaire. To the author’s own surprise, the quality of the obtained data was relatively high. The commonalities identified in the initial interviews were further established and expanded on while new ones were also identified.

The author acknowledges that the data collected does not lend itself to a true ecological inquiry. However, given the scope of the project, it was deemed sufficient to answer the given research question.

Analysis

As stated at the outset of this paper, the tourism industry has been one of the most impacted by the proliferation of ubiquitous Internet access. The Internet technology increasingly mediates the traveling experience by creating an online tourism information space – a collection of hyper textual content available for travel information searchers (Xiang, & Gretzel, 2010). While in the past the brands and travel agencies owned the sense of quality, now it is the digital word-of-mouth that decides where people go to eat, sleep and entertain themselves when on the road (Vanderbilt, 2015; Xiang, & Gretzel, 2010).

To guide the analysis, the following research question has been devised (as stated in the Introduction).

How to provide travelers with location-based information through harnessing collective knowledge of local residents by applying principles of information design?

The analysis follows a DSRM as outlined in the previous section. The analysis starts off by identifying problems with some of the current solutions. Using the models presented in the conceptual framework, the second sub-section aims to uncover some of the information behavior patterns in the traveling context and infer characteristic of an information system that would support these patterns. The analysis concludes by proposing an information system solution that addresses the information problem posed by traveling.

5.1 Current solutions

There is no shortage of services and tools that claim to help travelers find useful information, and provide insight into a local culture. However, from the collected data it was apparent that there are a few prevalent sources of information that people use when they are visiting a foreign country. Following is an analysis of problematic aspects of some of those sources.

Search engines (Google)

Google is a dominant source of travel-related information for the majority of people (Xiang, & Gretzel, 2010). Several respondents from the survey indicated that they use Google to get a general overview of the location they are traveling to. However, some of those respondents also mentioned that they find Google unsuitable for finding a more specialized and personalized type of information. This information source can be described as many-to-traveler, since there is no predominant group that provides the information (if we omit paid search results). Google supports an exploratory type of travel research and is a good starting point, but in the words of one of the respondents: “[the] results can be quite overwhelming”.

Paper guidebook

A traditional source of travel-related information. Its main advantage is a comprehensive overview of the country’s landmarks, culture, gastronomy, and local manners. However, guidebooks can quickly get outdated due to the limitations of the paper as a medium. This source can be described as business-to-traveler since it is created by a company. This increases a chance of biased content, since other organizations can pay to be included, or prioritized in the guidebook.

TripAdvisor

One of the most widely used services for looking up reviews and ratings for restaurants and hotels. It is primarily a traveler-to-traveler source. This may result in a diluted type of information because the majority of the user-generated content is created by tourists, not locals, who are more familiar with genuinely local attractions. Their feedback systems are susceptible to manipulation with a possibility to buy bogus reviews online (Smyth, Wu, & Greene 2010). The interface is menu-driven, and the content on the service is curated by an algorithm that is secretive and non-transparent (Vanderbilt, 2015). The service's main advantage is the diversity of opinions and reviews lowering the overall bias. But since the reviews and ratings are bound to a single, isolated attraction, the service runs into a trouble of generating “loads of info, but no insight” (Vanderbilt, 2015).

CouchSurfing

The service is not officially portrayed as a travel-related information source. Yet, it provides a local-to-traveler type of information exchange, which provides the traveler with most authentic information. However, this exchange happens exclusively through face-to-face communication. The online service serves only as a mediator, helping travelers establish a contact with a local host. It does not produce, nor capture any travel-related information artifacts for future reference for other travelers.

5.2 Information seeking and traveling

As mentioned earlier, online search using Google is the prevalent method of information seeking behavior when traveling. It is followed by asking someone that is familiar with the country the traveler is planning to visit. Some respondents prefer to use paper guidebooks, mostly in combination with some of the other methods. From the respondents’ answers, it was apparent that people value opinions of other people more highly than they value ratings, rankings, and other forms of algorithm-based metrics. This sub-section of the analysis applies the models presented in the conceptual framework to infer characteristics of a potential IS solution that addresses information problems in a traveling context.

Dervin’s Sense-Making Framework

Derwin’s Sense-Making framework is used to situate the traveler in time and space and identify means of resolving information problems they face in relation to the outcomes they expect to achieve. The first situation occurs in traveler’s home country when they first find out they are going to travel to a foreign country. It is at this point where first information problems arise. Travelers have to ask themselves questions like:

- Where am I going to stay?

- How am I going to get there?

- How much money do I need to take with me?

- Where am I going to eat?

- What things do I need to take with me?

Such questions represent a gap in knowledge and indicate an insufficient access to information. Travelers want to pick the best place to sleep, choose a restaurant with the tastiest food, or pack the most appropriate clothes. To achieve this, travelers have to find means of acquiring information necessary to bridge the gap between their situation and the desired outcome. In the first situation, prior to traveling, this gap is most often bridged by searching for information online, or asking someone who is familiar with the destination the traveler is visiting. This provides them with the information they need to achieve the outcomes later on when they are in a foreign country.

Travelers find themselves in different situations at various stages of their journey, and they use different bridges depending on the immediate context. For example, on an airport the desired outcome is finding the right gate and bridge is provided by looking up information on a flight departure display. Or when lost in a foreign city, asking someone on the street for directions serves as a bridge to getting to the desired location. The choice of bridges is thus highly situational and dependent on time and context. Based on this framework, the following two situations were chosen as key for the proposed IS solution:

- Planning a future trip to a foreign country using a desktop computer in a home country.

- Looking up directions to a specific location using a smartphone in a foreign country.

Limiting the number of situations for the proposed IS solution will provide focus, and should make the solution more sensitive to the immediate context of use.

Information Needs and Seeking

Information Needs and Seeking model is used to examine personal needs in a traveling context, followed by a brief examination of other factors influencing information behavior when traveling.

In his model of Information Needs and Seeking, Wilson (2006) identifies personal needs as a motivator for information seeking behavior. Despite the title of the model, Wilson argues that the term information needs is not adequate and that we instead speak of information seeking towards satisfaction of needs (Wilson, 2006). In this view, information needs are merely a way to conceptualize more basic human needs in relation to information and ways of obtaining it. The basic human needs are physiological, affective, and cognitive. These needs are closely interrelated. In a majority of situations, higher-level needs cannot be attained without satisfying lower-level ones (in the order they are presented here). However, for the purposes of this analysis, it is assumed that a traveler is in such life situation that allows him to fulfill all the needs equally.

Physiological needs – Physiological needs in the context of travel do not differ significantly from the physiological needs in a home country. People always need food, water, and shelter, no matter where they are. There is, however, one factor that seems to change when traveling. Many survey respondents mentioned information about restaurants and eating out as very important when planning a trip. This indicates that when traveling, people might have a higher standard for the quality of food. The same applies to accommodation, where people might expected a higher standard for room tidiness. This signifies that a certain indicator of quality should be included in the proposed IS solution.

Affective needs – Affective needs, sometimes called psychological or emotional needs, are hard to grasp because every person has virtually a unattainable number of them. Yet, there are some affective needs that are particularly important for the context of travel. The need for enlightenment and cultural self-development was one of the most apparent with the survey's respondents. Many have mentioned that they are interested in finding information about local culture and important historical landmarks. Other needs in this context may include entertainment, being in control, privacy, sense of belonging, security, feeling of competence, and many others. Travelers are going to prioritize those needs differently based on their personal preferences. It can be argued that certain patterns and categories will arise eventually. These patterns could be described using stereotypes like a lone traveler, adventurous traveler, family man, or travel snob. While this list is far from exhaustive, it implies that there are certain themes that reflect certain affective needs. This signifies that the proposed IS solution should incorporate elements that will make it easy to navigate based on themes.

Cognitive needs – The most high-level needs are the cognitive needs. Arguably, these needs are even harder to grasp than affective needs. They represent person’s drive to pursue new knowledge, learn new skills, and generally improve their intelligence and cognitive abilities. There were no clear references to cognitive needs in relation to traveling in the survey’s answers. The desire to learn about local landmarks and culture could be included here, but it was deemed more suitable to categorize it as an affective need. Wilson (2006) mentions the need to plan as an example of a cognitive need. It is this need to plan that is used for the subsequent analysis. Which signifies that the proposed IS solution should enable people to plan out their travels.

Other factors – In the model Wilson also stresses the importance of various environmental, contextual, personal, and interpersonal factors that affect people’s information behavior. Travelers face many constrains both prior, and after traveling to a foreign country. The most important are environmental constraints. Travelers base their key travel-related decisions on the time of the year, weather, or physical distance from their home. Economical constraints are also very important. Many respondents mentioned that they are interested in information regarding price levels. Some explicitly indicated interest in cheap places and money saving options. For some travelers, socio-cultural environment plays an important role as well. Some people might prefer to travel to places that are culturally similar to their home country. While some people might choose to explore different cultures and look for information that would give them such opportunity. Person's current social role is also a key factor in determining what types of travel-related information they are looking for. For example, some of the respondents mentioned that when they are traveling they look for kid-friendly destinations. In this case, a parent role significantly influences the information seeking behavior. The broad scope of the factors presented here signifies that the proposed IS solution should provide different ways of categorization.

5.3 Proposed Information System Solution

This sub-section offers a low-level conceptualization of an information system based on the analysis presented so far. Given the early stage of the design process, many details are omitted. In this early phase, the main goal is to establish a set of overarching principles, which will guide future iterations and development. These principles stem from general human-centered design approaches and more detailed examination of the information problems in a traveling context.

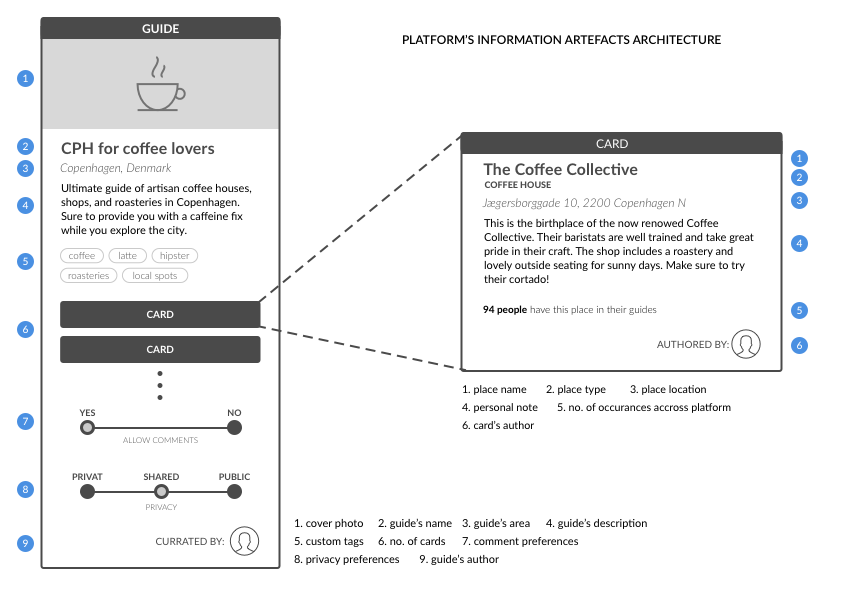

The solution is an online platform placed in an online tourism information space. This platform is populated with “information artefacts that enable and encourage people to understand the activity space” of travel (Benyon, 2001, p. 429). These information artefacts are referred to as “cards” and they contain personalized information about a specific location. Any user can create these cards; however they are primarily created by the local residents. Travelers than use a collection of those cards to gain insight and improve their knowledge of the destination they are traveling to. Users on the platform can also create lists that contain a number of cards. These lists are referred to as “guides”. Other users on the platform can browse, bookmark, and comment on those guides or choose to copy only certain cards to their own lists.

Compared to existing solutions, the user is not presented with a long predefined list of locations that would impose a certain structure on them. Instead, a creator starts with a blank slate and enters locations manually one by one. This design decision is based on the assumption that the “best information environments do not automate away the human role” (Choo, 2002, p. 50). This eliminates the need for advanced algorithms and lets a more organic structure emerge. Users become the main curators and exclusive carriers of qualitative judgment on the platform. Unlike with current solutions where the underlying technology tries to come up with best recommendations based on arbitrary and biased algorithms.

By letting everyone create their own cards from scratch, there will inevitably be numerous cards that are referring to the same location. From an engineering perspective this would be seen as duplicate content and would be considered ineffective and redundant. However, from an ecological perspective, this can be seen as a positive feature of the platform. It embraces variety and provides space for highly personal opinions that do not conform to homogeneous standards set by others.

The proposed design also addresses the problem of human scale. Many of the current solutions are overwhelming and cause information overload. For example on TripAdvisor, it is common to have several thousand entries for large metropolitan areas. The concepts of guides, on the other hand, makes the information easily digestible by always presenting information in isolated chunks, rather than an endless stream. This has an added benefit of inherently creating thematic categories for the platform with the mere act of creating a guide. Because everyone has certain set personality traits and interests, the guides created on the platform will always, to a greater or lesser degree, follow a certain theme. For example a person who enjoys jazz bars may also frequent specific kind of cafes. If this person creates a guide, another jazz fan from a different country can use it to visit a jazz bar and have a relatively high chance that they will enjoy cafes listed in that guide.

Despite the critique of screen-based interfaces presented earlier in the paper, the solution presented here is inherently bound to certain technologies. Currently, digital screens connected to the Internet are simply the most appropriate medium for conveying large amounts of information in an easily digestible form. By initiating the design with a low-level conceptualization informed by an ecological inquiry, the author hopes to mitigate some of the downsides of solutions based on the capabilities of the latest technology. Following are some of the key technical characteristics of the proposed platform:

- The platform should be Web-based, so it is accessible from a variety of operating systems and devices. Native applications are of secondary importance.

- When using the platform on a desktop computer, a user has to be able to freely reorganize and order their guides and cards.

- When using the platform on a smartphone, the user has to be able to download guides for offline use because data plans abroad are too expensive for most people.

- Creators of the guide have to be able to set the privacy of their guides to either private, privately shared, or public.

- Creators have to be able to disable comments on their guides.

Figure 11 - A proposed system's architecture

Conclusion

This paper traced back a history of human-centered design and its evolving role in society. It criticized techno-centric design methods and suggested that information design, rooted in ecological inquiry, is more suitable for coping with the problem of information overload. Models of information seeking behavior from a young field of Human Information Interaction were used to analyze information problems in the context of traveling to a foreign country. This analysis was used to conceptualize an online platform that would provide a more authentic traveling experience.

This paper represents a first stage in a long-term design process. Future research needs to conducted to create a high-level conceptualization, including elements of a visual interface. Further research is also needed to gain insight into models of motivation in information economy based on online peer production and possible business models for monetization of the platform.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Attila Marton for supervising this project and providing valuable feedback. The author would also like to thank all the interviewees and survey respondents.

References

Albers, M. J. (2008). Human-information Interaction. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (pp. 117–124). New York, NY: ACM.

Andreessen, M. (2015, January 2). Introduction (by Marc Andreessen). Retrieved August 3, 2015, from http://breakingsmart.com/season-1/introduction-by-marc-andreessen/

Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2012). Chapter 9: Information behaviour. In Introduction to Information Science (1st. ed). Chicago: Neal-Schuman Publishers.

Benyon, D. (2001). The new HCI? navigation of information space. Knowledge-Based Systems, 14(8), 425–430.

Burford, S. (2011). Complexity and the practice of web information architecture. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(10), 2024–2037.

Carmichael, M. (2011, November 9). Edward Tufte: The AdAgeStat Q&A. Retrieved August 2, 2015, from http://adage.com/article/adagestat/edward-tufte-adagestat-q-a/230884/

Choo, C. W. (2002). A Process Model of Information Management. In Information Management For The Intelligent Organization: The Art Of Scanning The Environment (3rd ed.). Medford, NJ: Information Today.

Cooley, M. (2000). Human-Centered Design. In Information Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Crotty, M. J. (1998). The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Detlor, B. (2010). Information management. International Journal of Information Management, 30(2), 103–108.

Dorte, M. (2012). New Directions in Information Management Education in Denmark: On the Importance of Partnerships with the Business Community and the Role of Interdisciplinary Theory to Create a Coherent Framework for Information Management. In Library and Information Science Trends and Research: Europe (Vol. 6, pp. 247–270). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Dreyfuss, H. (1955/2003). Designing for People. New York: Allworth Press.

eMarketer. (2014a, January 16). Smartphone Users Worldwide Will Total 1.75 Billion in 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2015, from http://www.emarketer.com/Article/Smartphone-Users-Worldwide-Will-Total-175-Billion-2014/1010536

eMarketer. (2014b, December 11). 2 Billion Consumers Worldwide to Get Smart(phones) by 2016. Retrieved May 17, 2015, from http://www.emarketer.com/Article/2-Billion-Consumers-Worldwide-Smartphones-by-2016/1011694

Fidel, R. (2012). Human Information Interaction: An Ecological Approach to Information Behavior. The MIT Press

Fidel, R., Pejtersen, A. M., Cleal, B., & Bruce, H. (2004). A multidimensional approach to the study of human-information interaction: A case study of collaborative information retrieval. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology.

Gócza, Z. (n.d.). Myth #21: People can tell you what they want. Retrieved May 13, 2015, from http://uxmyths.com/post/746610684/myth-21-people-can-tell-you-what-they-want

Graham, P. (2013, July). Do Things that Don’t Scale. Retrieved August 4, 2015, from http://paulgraham.com/ds.html

Gregorio, J. (2014, May 9). No more JS frameworks. Retrieved August 3, 2015, from http://bitworking.org/news/2014/05/zero_framework_manifesto

Hughes, M. (2002). Moving from Information Transfer to Knowledge Creation: A New Value Proposition for Technical Communicators. Technical Communication, 49(3), 275–285.

IBM Corporation. (2013, October 16). What is big data? Retrieved July 31, 2015, from http://www-01.ibm.com/software/data/bigdata/what-is-big-data.html

Internet Live Stats. (n.d.). Number of Internet Users (2015). Retrieved May 17, 2015, from http://www.internetlivestats.com/internet-users/#trend

Jacobson, R. (2000). Information Design (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Jones, W. (2012). The future of personal information management, Part I: Our information, always and forever. San Rafael: Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

Jones, W. P., & Teevan, J. (2007). Introduction. In Personal information management. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Klein, L. (2013). UX for Lean Startups: Faster, Smarter User Experience Research and Design (1 edition). Farnham: O’Reilly Media.

Kohr, L. (1957/2001). The Breakdown of Nations. Devon, UK: Green Books Ltd.

Krishna, G. (2015). The Best Interface Is No Interface: The simple path to brilliant technology (1 edition). Berkeley, California: New Riders.

Myburgh, S. (2005). Chapter 2: What is information work anyway?. In The New Information Professional: How to Thrive in the Information Age Doing What You Love (1st ed.). Oxford: Chandos Publishing.

Naumer, C. M., & Fisher, K. E. (2007). Naturalistic Approaches for Understanding PIM. In Personal information management. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Nonaka, I. (1991). The Knowledge-Creating Company. Harvard Business Review, 69(6), 96–104.

Papanek, V. (1972/1985). Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change (2nd. ed.). London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Papanek, V. (1983). Design for Human Scale. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

Papanek, V. (1995). The Green Imperative: Ecology and Ethics in Design and Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Peffers, K., Rothenberger, M. A., Tuunanen, T., & Chatterjee, S. (2007). A design science research methodology for information systems research. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(3), 45–77.

Pirolli, P., & Russell, D. M. (2011). Introduction to this special issue on sensemaking. Human-Computer Interaction, 26(1-2), 1–8.

Schiff, E. (2015, April 7). Fall of the Designer Part I: Fashionable Nonsense. Retrieved August 3, 2015, from http://www.elischiff.com/blog/2015/4/7/fall-of-the-designer-part-i-fashionable-nonsense

Schlögl, C. (2005). Information and knowledge management: dimensions and approaches. Information Research: An International Electronic Journal, 10(4), 235.

Schumacher, E. F. (1973/1993). Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. UK: Random House.

Shedroff, N. (2000). Information Interaction Design: A Unified Field Theory of Design. In Information Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Smyth, P. C. B., Wu, G., & Greene, D. (2010). Does TripAdvisor Makes Hotels Better? Retrieved from http://www.csi.ucd.ie/files/ucd-csi-2010-06.pdf

Tsoukas, H. (2003). Do we really understand tacit knowledge? In The Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management. London: Blackwell.

Vanderbilt, T. (2015, March 13). Inside the Mad, Mad World of TripAdvisor. Retrieved May 3, 2015, from http://www.outsideonline.com/1960011/inside-mad-mad-world-tripadvisor

Weatherhead, R. (2014, February 28). Say it quick, say it well – the attention span of a modern internet consumer. The Guardian. Retrieved August 1, 2015, from http://www.theguardian.com/media-network/media-network-blog/2012/mar/19/attention-span-internet-consumer

Wilson, T. D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249–270.

Wilson, T. D. (2000). Human Information Behavior. Informing Science, 3(2), 49–56.

Wilson, T. D. (2006). On user studies and information needs. Journal of Documentation, 62(6), 658–670.

Wroblewski, L. (2011). Mobile FIrst. New York: A Book Apart.

Xiang, Z., & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31(2), 179–188.

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1 - Diagram of people involved in building a house and their relationship to the end occupant. Adapted from Papanek (1995)